By Richard K. Munro

Chapter two “With God Came Letters and Numbers”

Christianity came relatively late to the pagan Anglo-Saxons of whom it was said, “Neither numbers, nor letters, nor God.” Missionaries from Roman Britain spread Christianity to the Scotti (Gaels) of Ireland and the Picts of Scotland (St. Patrick c 432, St. Columba c. 563 and St. Mungo c 560. for example) thus preserving the ancient faith and knowledge of schooling, books and the Roman alphabet. [1]

In turn, these Celtic missionaries reintroduced Christianity to southern Britain –now known as England- and the Latin alphabet to the Anglo-Saxons. The Irish Gaels were instrumental in this time period in fomenting education and Christianity not only in England but on the continent as well planting an early missionary base on Lindisfarne Island as well as schools in Charlemagne’s empire (present day France, Germany and Switzerland). [2]

Figure 9 THE ROMAN ALPHABET The Latin alphabet originally had 20 letters; the Romans themselves added K plus Y and Z for loan words transcribed from Greek.

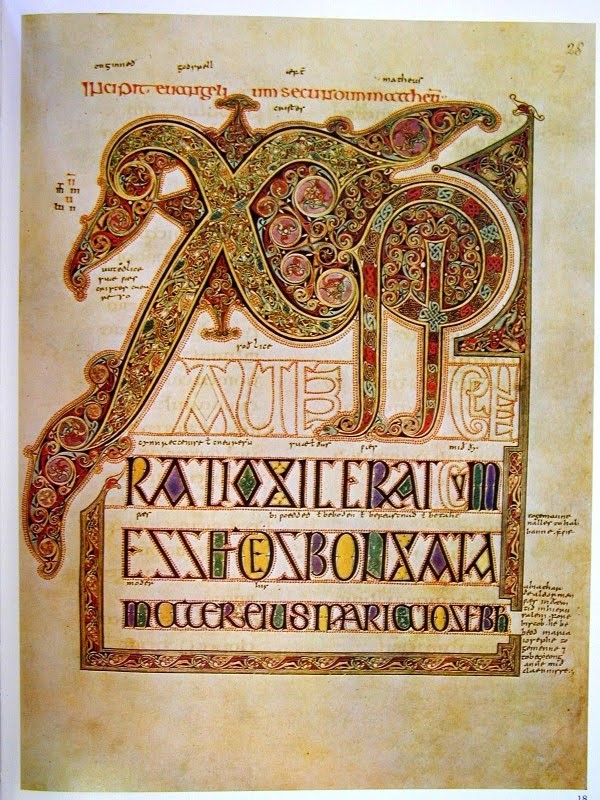

Figure 10 Book of Kells

Another force in Christianizing the Saxons came from Rome beginning with the mission of St.Augustine to Aethelbert, King of Kent, in AD 597. Aethelbert was chosen because he was married to a Frankish Christian princess[3] who encouraged the new religion. The story goes that Aethelbert, afraid of the powers of the Christian “sorcerers”, chose to meet with them in the open air to ensure that they wouldn’t cast a wicked spell over him! In any case, St. Augustine, “the Apostle of the English” laid a solid cultural foundation for English Christianity and the English language.

Augustine’s original intent was to establish an archbishopric in London, but at that time the London English were hard-core pagans, slavers and polygamists and so were very hostile to Christians. Therefore, Canterbury, the capital of the Kentish kingdom of Aethelbert, became the seat of the pre-eminent archbishop in England. The Church was a very important force in medieval English society. It was the only truly national entity –international really- tying together the various warring Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. It is significant to report that no written records of the Anglo-Saxon language survive from before the seventh century AD. The earliest substantial literature of the Anglo-Saxons is Beowulf[4]:

O flower of warriors, beware of that trap.

Choose, dear Béowulf, the better part,

eternal rewards. Do not give way to pride.

For a brief while your strength is in bloom

but it fades quickly; and soon there will follow

illness or the sword to lay you low,

or a sudden fire or a surge of water

or jabbing blade or javelin from the air

or repellent age. Your piercing eye

will dim and darken; and death will arrive,

dear warrior, to sweep you away.”

(translation Seamus Heaney)

If the Anglo-Saxons had remained pagan it is possible that their language may never have been widely written and so may not have survived its many travails.

Figure 11 Lindisarne Gospels

Anglo-Saxon England’s most famous historian and Doctor of the Church , the monk Bede, known as the Venerable Bede, lived most of his life at the monastery of Jarrow, in Northumbria (died 735). Nearby, the monastery of Lindisfarne is famous for its’ celebrated hand-colored illuminated Bible, an 8th century masterpiece of Celtic- inspired art, which is now in the British Library.[5] Lindisfarne Gospels, is a Latin Vulgate text with interlined Old English paraphrase. So it is very important in the history of the English language.

This is evidence that the Masses were given in Latin but the sermons were given (usually) in English. King Alfred’s circle of (Old) English-speaking teachers (Plegmund, Waerferth, Aethelstan, and Werwulf) led to a late 9th century revival of learning in Latin as well as the growth of Anglo-Saxon literature. The Anglo Saxon Chronicle, for example, was written in Old English not Latin). Alfred the Great’s unique importance in the history of English letters came from his conviction that a life without knowledge or reflection was unworthy. Alfred’s enthusiasm to spread learning to the people in English may have been a turning point for the survival of English. Under the auspices of Alfred the Great church schools were encouraged for common people, and many Latin works were translated into English. English was becoming a literary language and a language of local commerce. French was still important for the nobility and Latin for higher education but English soldiers, sailors and merchants continued to speak, to sing and to pray in English among themselves. And, increasingly, keep records and write in English. English became strong enough even to survive the catastrophic subjugation of the English which came after 1066.

Figure 12 Manuscript of Beowulf (Anglo-Saxon)

During this time the influence of Church Latin and St. Jerome’s Latin version of the Bible (known also as the “Vulgate” was colossal. Churches were almost the only forum for higher education[6] during the middle Ages. The higher church officials also played important secular roles; advising the king, witnessing charters, and administering estates of the church, which were extensive. The Magna Charta (1215) was written in Latin and so was the Scottish Arbroath Declaration of 1320. Previously Anglo-Saxon had a few Latin words most of them products or indicating spheres in which the Romans excelled such as road-building, commerce, travel and communication. These early Anglo-Saxon borrowings from Latin or Greco-Latin include, anchor, butter, candle, chalk, cheap[7], cheese, kettle, kitchen, to cook, dish mile, mint, crisp, pepper, port, pound, sack, school (originally Greek) ,shrine, street (paved road), tile and wall. Now with the introduction of a literate Latin Christian culture we have many new words (many originally Greek like the word Bible meaning in Greek “books”)[8] Hundreds of words come into English at this time from Latin and here are just a few: altar, apostle, circle, crystal, monastery, martyr, monk, nun, priest, clerk[9], commandment, devil, demon, relic, cat, fork, creed, mass, camel, psalm, paper, chapter, verse, lily, temple, and trout.

The early monasteries of Northumberland were vital centers of learning and the arts until they were wiped out by savage Viking raids of the 9th century.[10] Much of England, Ireland and Scotland were conquered by the Vikings (c.800-1263) but the Vikings dominated the off shore islands, the sea and the coasts not the hinterland.

![raid[1]](https://spiritofcecilia.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/viking-attack.jpg?w=250)

Figure 13 Viking attack on Christian monastery

The northern dialects of English were very influenced by Old Norse (an ancestor of Norwegian and Swedish but Germanic like Anglo-Saxon). Some examples of Old Norse (Viking) words are fellow, hit, sly, take, skirt, scrub, gill, kindle, kick, get, give, window, skipper, sister, thrall (slave),earl(warrior/noble), want and dream (it meant ‘joy’ in Anglo-Saxon.). [11] Yet despite these sporadic attacks both English and Christianity set deep roots. I cannot but help think that the Vikings were vanquished not only by the sword but by the faith and virtue of young Christian maidens with whom the Norseman cohabited and later married. In time language and religion assimilated and transformed the invader.

[1] After its adoption by the English, this 23-letter Roman alphabet developed W as a doubling of U and later J and V as consonantal variants of I and U. The resultant alphabet of 26 letters has both uppercase, or capital, and lowercase, or small, letters.

English spelling is essentially based on 15th century orthography, but pronunciation has changed considerably since then, especially that of long vowels and diphthongs.

[2] See Thomas Cahill’s charming small book How the Irish Saved Civilization

[3] Named Bertha

[4] Beowulf, Seamus Heaney, trans. ( New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2000)

[5] Older than this are the Book of Kells, its inspiration which was probably created in Iona generations before.

[6] Almost entirely in Latin.

[7] Cheap comes from the Latin caupo meaning “wine-seller”; a Chapman was original a merchant.

[8] Of course, the Anglo-Saxons called the Bible the Gospels, or the Good Book or the Old Book; these are expressions still used in modern English today.

[9] In Britain “clerk” is pronounced like “Clark” as in Clark Kent (Superman); it almost sounds like “clock”.

[10] There was an ancient prayer known round the Isles that went like this: A furore normannorum libera nos domine (“From the fury of the Norsemen deliver us, O Lord!”).

[11] Thomas Pyles and John Algeo The Origins and Development of the English Language Harcourt Brace, 1982 p299-300.

You must be logged in to post a comment.