“Do you think,” said Candide, “that mankind always massacred one another? Were they always guilty of lies, fraud, treachery, ingratitude, inconstancy, envy, ambition, and cruelty? Were they always thieves, fools, cowards, backbiters, gluttons, drunkards, misers, vilifiers, debauchees, fanatics, and hypocrites?”- Voltaire, in Candide, Ch 21

Category Archives: Republic of Letters

Economics and the Good: Part I

How does the discipline of economics approach ethical issues? A standard answer goes something like this. We can separate economics into two categories. Positive economics concerns itself solely with explaining the social world. Normative economics deals with moral concerns in a way that may build upon, but cannot be reduced to, positive economics. In other words, positive economics deals in statements of is; normative economics, of ought.

An important concept that acts as a bridge from positive to normative economics is economic efficiency. In reality, economic efficiency can mean several things. The strictest definition of efficiency is that no individual can be made better off without making at least one individual worse off. An alternative way of phrasing this is that all potential gains from exchange have been exhausted. Another definition of efficiency, one not so strict, is that the dollar value of society’s scarce resources has been maximized. Frequently these criteria go together, but they do not have to.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. We still need to explore how efficiency is operationalized. Positive economics can say whether a given situation is efficient or not. It cannot recommend efficiency as a value, of course, without losing its purely positive status. Normative economics frequently invokes efficiency as a standard against which economic outcomes are judged.

However, economists frequently get into trouble when they make statements about efficiency that contain both positive and normative elements without realizing it. Consider the following thought experiment. Allan is auctioning off an apple. Bob and Charlie both bid for the apple. Bob bids $1, and Charlie bids $2. Allan gives the apple to Charlie. Note that this is an efficient result, in both the strict and the loose sense. (Instead of letting the results of the auction stand, we could take the apple won by Charlie and give it to Bob. That would make Bob better off, but would make Charlie worse off.)

What if Allan knowingly gives the apple to Bob instead of Charlie, voluntarily accepting $1 instead of $2? This situation seems inefficient in the looser sense. But as long as secondary bargains are not forbidden, Bob can always sell the apple to Charlie. Since Bob bid only $1, whereas Charlie bid $2, at any price for the apple above $1 and below $2 there is room for a mutually beneficial exchange. Either way, the apple will end up with the person whose valuation of it is highest in dollar terms.

Why is this dangerous territory? Because economists themselves frequently forget the boundaries of each kind of efficiency. If Allan gives the apple to Bob, economists will often say something like, “That’s inefficient; the apple should go to Charlie.” Furthermore, they frequently would support something like a redistributive policy that reallocates the apple from Bob to Charlie. Even if they don’t support that particular policy, they would endorse efficiency as a valid metric for determining public policy, asserting that such policy “merely helps people get what they want.” And economists will do so thinking they are still doing purely positive economics. Clearly any issue pertaining to the distribution of goods and services beyond the purely descriptive is normative, in that it involves value judgments. The problem is the concepts economists work with, and the way they apply those concepts, makes it hard for even careful economists to know where descriptive economics ends and prescriptive economics begins.

You may have noticed two controversial statements in the above explanation. The first is that efficiency should be a criterion for crafting public policy. The second is that promoting efficiency, because it means giving people what they want, is not controversial. But both of those statements are in fact normatively loaded. I will explore further how and why economists overlook these issues in subsequent posts.

In Defense of Historical Complexity: A Meditation on the Old South

“Sing me a song of a lass that is gone,” the Outlander theme song begins (“The Skye Boat Song”). The show, based on Diana Gabaldon’s romantic history novels, depicts a lost world of 18th century adventure, Scottish highland clans, and loyalty shaped around various allegiances. The protagonist, Claire, is a 20th century woman who has been cast back in time to the different world of 18th century Scotland; she is the “lass” of the title song. At the same time, “lass” symbolizes the whole world of excitement that Claire finds herself living. The world of the past “is gone,” and Outlander is a song contrasting modernity with a specific moment in the past.

In the midst of such a contrast, what is the person with an active historical imagination called to do? Does the past become an extended store of ethical examples demanding moral judgement? Or is there something more to developing an imaginative vision of an alternative time? I propose that there is something more, and that at a minimum an engagement in a formal study of the past should begin with understanding which moves to love. Rather than asking “Were X-group-of-people right or wrong to do Y-action?” the proper historical question is “Why did X believe they should do Y, and what can we find that is admirable in their choices or convictions?” Permit me to illustrate this approach to history using the antebellum and Civil War eras (roughly 1848-1865).

As a boy growing up in Virginia, I developed a love for the Old South. The remnants of the material culture of the South were all around me – historical signs, the iron factory in Richmond, VA., battlefields of minor victories and substantial losses. But perhaps the most formative encounter I had with a vision of southern culture came from the novel Gone with the Wind. One summer I set myself the goal of reading a novel of more than 1000 pages, and the romance of Scarlett and Rhett, the fate of Tara, and the fight to defend home and live in the aftermath of its loss captivated my imagination. Here was a different world, filled with different values, different reactions, different dreams than my own; here was a way of life people fought to protect.

As I grew older, I began formally studying the events of the Civil War. I learned about sectionalism, the economic systems which enabled both the high plantation lifestyle and the poor white farmer to coexist, the evils of slavery, and division which threatened to wreck the Union. I read sermons from pastors in the North who drew from their theological traditions a deep respect for the dignity of the human person to support the abolitionist cause; and then I read speeches from southerners who saw in their aristocratic hierarchical society the hand of God locating each person within a specific place for the good of the body politic. Reading first hand accounts and scholarly interpretations, I observed the complexities of the moment. Stalwart men of virtue (Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson) fought for their homes, their land, and their way of life. Northern generals (Tecumseh Sherman and Ulysses S. Grant) lacked virtue but delivered victories through their scorched earth, “rape of the south” give-no-quarter tactics. Not only did the North win the war, but in doing so the Union set southern economic activity backwards by over a century.

The complexities of this era fascinated me, and to this day I get passionate when confronted with simplistic understandings of the Civil War. This struggle was about slavery, but that issue represented a constitutional question. Could the states break the Union? Which was primary: the people, or the states? Secondarily, this war was also the struggle of two different economies: agrarianism vs. industrialism, and the life of the farm vs. the life of the city. Wrapped into these political and economic concerns were substantial philosophical questions: do all human beings have dignity? If so, how does that dignity work itself out in political life? What is the nature of governing authority? Is it bound by the Constitution? Can the highest authorities violate the source of their authority for a good purpose? What does it mean to be created “equal?” Paired with philosophy, politics, and economics were the rise of abolitionist rhetoric and the power dynamics of an entrenched 19th century racism. These complexities resist simple answers.

Between 1848 and 1865, the United States engaged in a trial by combat to answer fundamental questions. By the end of the Civil War, several questions received answers sealed in blood: the states were subordinate to the Union, the people were the primary political power in the United States, equality meant equal freedom and self-responsibility before the law, and the American economy was one of increased industrial, urbanized patterns of material production and consumption. The South lost, and in its loss passed a way of life. Rather than settling the conflicts once and for all, Northern victory only deepened the complexities which brought the United States to this point. Studying the Civil War era must be more than a formal engagement in condemning the practice of slavery; such a study should be an opportunity to grow in understanding and love.

Historical study begins with seeking understanding through primary text engagement. Reading the works of John C. Calhoun, Jefferson Davis, Abraham Lincoln, Stephen Douglas, Robert E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant, and the other men of the day emerses the student in the richness of that other moment. For good or ill, these were real men and women seeking to live life well, and in coming to understand their motivations we are moved not to agreement, but to love. It rather resembles a wayward brother – by understanding the choices my brother has made and the circumstances which motivated those choices, I develop a compassion, a desire to suffer alongside him. Were I to teach an American Civil War class, I would not expect students to agree with Southerners (or Northerners necessarily), but I would expect them to search out the motivations which caused hundreds of thousands on both sides to march against each other. And if we reach the level of understanding, a love for fellow human beings is the natural outgrowth of historical study.

Reading of the antebellum South is rather like reading Homer’s Iliad for the first time. One goes to it knowing the Greeks win, but the nobility and grace of Hektor in contrast to the puerile childishness of Achilles forces the reader to sympathize with the doomed city. The South fell, and, for many reasons, rightly so. It’s economic system was untenable: large parts of Southern life were based on a racist anthropology, and failed to align with reality; agrarian life could not keep pace with the technological productivity of an industrialized economy. At the same time, the cultural loss in the post-1865 South was real, and the costs of that loss merit remembrance. The southern way of life, rooted in the seasons necessary for agriculture and bound up with values of honor, delicacy, and hierarchy contained goods no longer found in American patterns of living. It is only by appreciating the value in what was lost that we see the price of “progress,” and in that sense the history of this period is as tragic as it is victorious in terms of moral or political philosophy.

The tension in how we view the Civil War era and its aftermath came to light in recent years with the publication of Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman. Lee tells the story of an adult Scout who returns home to Atticus and learns that her father is more complex than she remembers. The book troubled many who read it, because they expected the simplistic dialectic of To Kill a Mockingbird to return; instead, Lee presents us with a realistic racially minded Atticus Finch, a man who is concerned that African-American progress is happening too fast and causing essential change to the civilization he loves. To Kill a Mockingbird is a beloved classic. Who does not find his heart soaring in Atticus’ defense of Tom Robinson? But when Lee forces us to see that Atticus is a more complex figure, it causes the reader to wrestle with the question of change. How should change occur? At what pace should things change? And when change become the new norm, can we not pause and remember what was?

There is also the opposite danger. The Southern Agrarians (including one of my intellectual heroes Richard Weaver) romanticized the South, and in doing so constructed their critique of modernity on shaky ground. This romanticization is also bad history. Here Aristotle provides sound advice: moderation in all things. We cannot glorify the South or embrace the Myth of the Lost Cause; neither can we reduce the Civil War to a triumphant crusade to liberate the slave. The truth of the period will be found in the heart of its complexities.

“Sing me a song of a lass that is gone” encapsulates the enduring attraction of the South. Indeed, the old South has died, and in its death a greater equality for all Americans has developed. It remains for the historian not to pass on a catechesis ensuring that all students understand that the abolitionists were right, but rather to cultivate a desire to understand why the Civil War occurred, and in that understanding that we might exercise “the love which moves the sun and other stars” towards our benighted past.

Christ Pantocrator

The Coming Bankruptcy of the American Empire | The American Conservative

I had the chance (privilege) to meet Hunter a year or so ago. He’s a truly fine young man with a great career ahead of him.

The Coming Bankruptcy of the American Empire | The American Conservative

— Read on www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/the-coming-bankruptcy-of-the-american-empire/

By Way of Introduction…

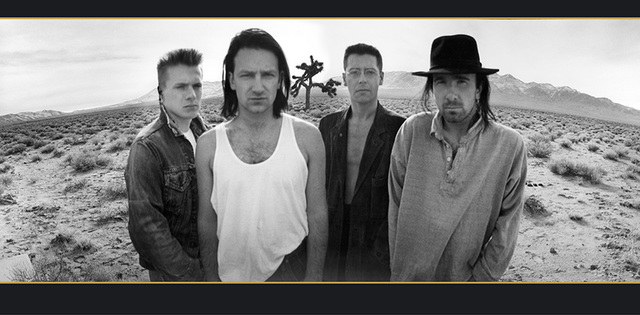

Earlier this year, I was surprised and honored to be asked by the National Recording Registry of the United States Library of Congress to write a short essay to accompany one of the works listed, U2’s landmark 1987 album The Joshua Tree. As a way of breaking the ice on my contributions to Spirit of Cecilia, I thought I would share that essay here. Writing it gave me the opportunity to re-connect, in a somewhat limited and wistful way, with a band that has meant a lot to me over the years. The last couple of U2 albums, despite a few great moments and the occasional flashes of brilliance, have left me cold. I was further disheartened by U2’s glib, corporatist support of the unlimited abortion license, which was deftly (and devastatingly) critiqued by Irish journalist and playwright John Waters over at First Things. This is the kind of terrain I am most likely to cover on this blog, trawling the megahertz in search of Godly inspiration in the devil’s music.

Earlier this year, I was surprised and honored to be asked by the National Recording Registry of the United States Library of Congress to write a short essay to accompany one of the works listed, U2’s landmark 1987 album The Joshua Tree. As a way of breaking the ice on my contributions to Spirit of Cecilia, I thought I would share that essay here. Writing it gave me the opportunity to re-connect, in a somewhat limited and wistful way, with a band that has meant a lot to me over the years. The last couple of U2 albums, despite a few great moments and the occasional flashes of brilliance, have left me cold. I was further disheartened by U2’s glib, corporatist support of the unlimited abortion license, which was deftly (and devastatingly) critiqued by Irish journalist and playwright John Waters over at First Things. This is the kind of terrain I am most likely to cover on this blog, trawling the megahertz in search of Godly inspiration in the devil’s music.

Poetry, Oblivion, and God | The Russell Kirk Center

Poetry, Oblivion, and God | The Russell Kirk Center

— Read on kirkcenter.org/reviews/poetry-oblivion-and-god/

Ep. 1285 The Establishment Is Ignorant: Nullification Edition | Tom Woods

Ever since it became known that acting Attorney General Matthew Whitaker has spoken favorably about the right of the states to nullify unconstitutional federal

— Read on tomwoods.com/ep-1285-the-establishment-is-ignorant-nullification-edition/

Expanding the Pallette

Before I begin this introductory piece in earnest, I would like to take a cue from Tad Wert’s excellent piece about The Underfall Yard and display some gratitude. A little over six years ago, one of this site’s founders, Brad Birzer, co-founded another site called Progarchy.com. While dedicated to music in general, as it’s title would suggest, it’s emphasis was on my favorite musical genre, progressive rock. Not long after the site went live, I left a comment there that grabbed Dr. Birzer’s attention. The next morning, an email expressing thanks for the comment arrived in my inbox. We exchanged a few more emails and promised to enjoy a beer together if we ever met in person.

But that was far from the end of it. Only moments after that exchange ended, I received another email, this time with an invitation to be a contributor at Progarchy. Having more than a few opinions about my favorite music, I jumped at the chance to write there, and I was off and running. Still, I’ve never forgotten how I ended up there, and thus my decision to follow Brad here was made before the invitation email arrived.

As for me? Professionally, I’m a patent agent, which can be thought of as a patent lawyer sans law degree/state bar admission. By education, I’m an electrical engineer, so the patent applications I write and prosecute are related to computers, electronic circuits, things like that. Some of you are probably reading this on a device that has some stuff inside for which I wrote the patent. I’m also a Navy veteran, having served six years as a sonar technician on the nuclear-powered submarine USS Olympia, with the entirety of my enlistment served under the best commander-in-chief of my lifetime, Ronald Reagan.

Personally, I have a wife who originally hails from Koga, Japan (about an hour north of Tokyo by train), and most importantly, an eight year old son who is one incredible kid. It’s possible that he’s a bit spoiled, although I have absolutely no idea whatsoever how that happened (insert faux-innocent facial expression here).

Now to tie things up, I do a lot (and I mean, A LOT) of writing in my day job. That writing is primarily an amalgamation of technical and legal writing … with emphasis on the technical … and the legal. One of the joys of being a contributor at Progarchy was that I was able to write about something I loved, music. Here, I get to do the same, and more. I’m sure topics of many future posts will be musical in nature, but this site offers me a chance to write about other things. I’ve already got a few ideas bouncing around in my head. Please accept my apologies for the rattling noises.

In closing, I’d like to thank the founders of this site for having me. It’s truly an honor.

Just the Beginning…

Studying history at the graduate level has taught me a very important fact: life without Jesus Christ is sad, dark, depressing, and meaningless. I am drawn to the history of Christianity in my research. Over the last year or so, that has included “third great awakening” revivalism, with a specific emphasis on D. L. Moody. But in readings for traditional history classes, the focus is often upon slavery and oppression. Nuance is all but absent in the post-Foucault discipline of history, and this has bothered me a lot because even the best people are capable of both good and evil. For a variety of reasons, the academy has chosen to throw out all of the good in western thought because of some instances of horrible injustices (injustices which are in fact antithetical to western principles). One of the reasons I’m excited about Spirit of Cecilia is because this site is hopeful. We understand that there is goodness in the world, and there are ideas that God placed inside of us that are worth protecting and preserving.

So who the heck am I?!

Well as you’ve probably gathered, I’m a graduate student. I’m in the second year of a Public History MA program at Loyola University Chicago, and I plan to work in museum collections. I interned this past summer at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum in Grand Rapids, MI. Working there confirmed for me that I really enjoy collections work. It is very rewarding. Thankfully, most of my classes in Public History are more practical than traditional history in the sense that they are preparing me to work in public history settings such as museums, oral history projects, national park service, archives, historical interpretation, etc.

I earned my BA in history from Hillsdale College, where I had the honor of having one of Dr. Brad Birzer’s magnificent classes on Christian Humanism. He was kind enough to invite me to write for Progarchy back in 2013, and that sent me headlong into the contemporary progressive rock genre. I’m very grateful that he asked me to be a part of this new internet venture. I hope to contribute to its excellence in whatever small way I can.

You must be logged in to post a comment.