On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the late John Paul II’s birth, it’s worth underscoring that one theme which permeated his pontificate from its beginning to the end was that of truth.

Many remember Pope John Paul II as playing a crucial role in Eastern Europe’s liberation from Marxist tyranny. But he also insisted that liberty needed to be grounded in and guided by the truth knowable via reason and faith. If freedom and truth become separated—as they most certainly have in many people’s minds in our own time—we not only end up with an unhealthy and dangerous association of liberty with moral relativism. We also open the door to those who claim that the truth is whatever the most powerful or the loudest say it is.

— Read on blog.acton.org/archives/116144-how-john-paul-ii-reminded-us-that-liberty-and-truth-are-inseparable.html

Chapter Three the NORMAN CONQUEST transforms English

By Richard K. Munro

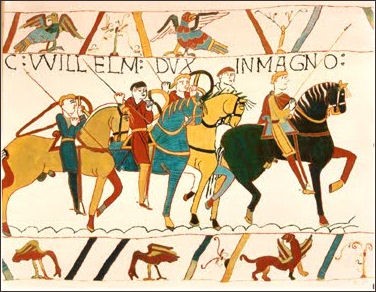

Figure 1 William the Conqueror

In 1066 the Normans, under William the Conqueror, invaded England and killed the last king of the Anglo-Saxons, Harold, at the Battle of Hastings. There are no loanwords of unquestionably French origin that occur prior to 1066. Conquered by the Normans, the Anglo-Saxons, essentially, ceased to exist as an independent people from that time.[1] The Anglo-Normans spoke French and used it as a language of administration; they also learned Latin for the Church and the Universities. There are thousands of French loanwords in English and no language has influenced English so much except Latin (and of course French is a romance language derived from Latin as Spanish is). Much of early common law, however, was written in French. But the language of everyday community life and commerce in England during this time (1215-1400) remained English.

English might have died out completely except for the fact that England, being part of an island, was separated from France and tended to thus be isolated. England and France –cousin nations really- fought many wars for supremacy. At one time England claimed and occupied most of France. The ruling families which continued to speak French until abut the 1350’s. But the merchant classes spoke an English-French patois and enjoyed songs and literature in that idiom. Chaucer wrote the Canterbury Tales in Middle English using thousands of French borrowings. Chaucer was fluent in French and competent in Latin. Gilbert Highet says “He does not seem to have been a university man, and indeed there was something amateurish about his learning; but it was good for his poetry.”[2] Some of his words may have come from Latin but most come from French, it seems to me. That because Chaucer often follows French spellings such as “absence” and “ignorance” rather than the Latin “absentia” and “ignorantia.” Also we note that Greek words are present –Chaucer did not know Greek- but at a much smaller proportion as compared to Latin and most of these are Hellenic words which were already Latinized by the medieval Church fathers, Cicero or the Roman Stoic philosophers. The Legend of Good Women [3] the third longest of Chaucer’s works, after The Canterbury Tales and Troilus and Criseyde is the first significant work in English to use the iambic pentameter or decasyllabic couplets which he later used throughout the Canterbury Tales. A couplet is two successive rhymed lines that are equal in length; a heroic couplet is a pair of rhyming lines in iambic pentameter. This form of the heroic couplet, inspired by French literature[4] and popularized by Chaucer would become a significant part of English literature. Shakespeare often has his characters speak a heroic couplet before exiting: The time is out of joint: O cursed spite/ that ever I was born to set it right. “(Hamlet Act 1 scene 5)

Chaucer is not easy to read today without a glossary but it is quite remarkable that sometimes he is completely intelligible so close he is to modern English. His spelling is different and his pronunciation would sound strange or rustic to us but it is clearly English. Originally, the long vowels of Old English (Anglo-Saxon) were essentially the same as those found in Latin but gradually the values of English vowels shifted. These changes in the quality of the long, or tense, vowels constitute what is known as the Great Vowel Shift. In other words the vowels of Chaucer are closer to Latin or “Continental” and the sounds of English have gradually changed causing pronunciation and spelling problems. “The stages by which the shift occurred and the cause of it are unknown. There are several theories, but the evidence is ambiguous.”[5] We don’t know why it happened but I will venture a guess: in the long periods of bilingualism in England (meaning French and Anglo-Saxon (Old English and Middle English) the English people mixed and matched sounds from different languages. This is a process which still goes on today; an example would be the world “rodeo” which can be pronounced in the Spanish fashion or in a “Western” American fashion. Note that, while Chaucer’s pronunciation of the long vowels was quite different from ours, Shakespeare’s pronunciation was similar enough to be comprehensible thought it might sound -I have heard said- rather “Irish” or “rustic” or exotic to our ears. Prior to the Great Vowel Shift, which Chaucer rhymed food, good, flood and blood (sounding similar to goad or a long ō like boat). By Shakespeare’s time the three words still rhymed, although by that time all of them rhymed with food (ū like mood). This pronunciation would sound perhaps Scottish today. In American English, particularly works like look, book, nook, as well as good, flood and blood have independently shifted their pronunciations again. Note it is not INCORRECT to pronounce the words in the “old fashion” but today they would be considered “regional” pronunciations.

GREAT VOWEL SHIFT CHART (AHD phonetics with examples)[6]

| Word | ME CHAUCER | 1600 SHAKESPEARE | Standard American English | (British 21st century)RP |

| house | Ū (like “hoose” or “moose”or “goose” | ou like “blouse” | Ou | ou dialect “hoose” Canada; Scotland |

| food | Ō like “Goad or boat” | Ū like mood | Ū like mood | Ū like mood |

| boat | ō | ō | ō | ō slightly longer than American English |

| size | ī | aI (ī) dipthong | aI (ī) | aI (ī) |

| green | ĕ | Ē (like seen) | Ē Note been ≠seen | Ē Been=seen |

| meat | Ā (like “mate” or “hate” | Ē like “heat”, “Feet” | ē | ē |

| bake | ă | ā | ā | ā |

| good | Ō like “Goad or boat” | Good like hood |

Here are some examples of Chaucer followed by modern English:

“He knew the tavernes wel in every toun”

(He knew the taverns well in every town)

(Canterbury Tales. Prologue 1. 240)

“And gladly wolde he lerne, and gladly teche.” (Ib. 1, 308)

(and gladly would he learn and gladly teach)

“The carl spak oo thing, but he thoghte another.”(Ib. The Freres Tale 1, 270)

(The Churl (Guy; hick) spoke (spake) one thing but he thought another)

She was fair as the rose in May (Legend of Cleopatra 1.34)

(She was as fair –beautiful as the rose in May)

For of fortunes sharp adversitee

The worst kinde of infortune is this,

A man to have ben in prosperitee

And it remembren, when it passed is.

(Troilus and Criseyde 1, 1625)

For of fortunes sharp adversity

The worst kind of misfortune is this:

A man to have been in prosperity

And it remembered, when it passed is.

Yes, this English but it has a Germanic flavor: “when it passed is.” It is amusing to recall Spencer said that Chaucer, of all people, was a “well of English undefiled” (unpolluted). Gilbert Highet has written “the importance of Chaucer was that he became not only a well of pure English but a channel through which the rich current of Latin and a sister stream of Greek flowed into England”[7] (via as we have seen chiefly through French). The last quotation is very interesting due to the syntax. It says “fortunes sharp” rather than “sharp fortunes” –this is the influence of Latin or French where it is typical for the adjective to follow the noun. “Infortune” exists, I suppose in the English lexicon but must be considered unusual or archaic; the normal word here would be “misfortune.” Of course, “ben” is spelled “been” today (but pronounced two ways; the American “bin” and the British “be-en” as in bean). And when Chaucer uses “remembren” rather than “remembered” he is using the old Anglo-Saxon past participle; cf. “spoken”, “taken” or “forgotten”. Most modern English verbs have lost the –en suffix in the past participle though we have some adjectives that do retain it as in “sunken ships” or “drunken fool.”

The London dialect, for the first time, begins to be recognized as the “Standard”, or variety of English taken as the norm, for all England. Other dialects are relegated to a less prestigious position. Over the years the Anglo-Norman French of the ruling classes created an English-French patois with a vocabulary that was heavily Latin and French and a very simplified grammar and inflectional system. For example, English lost its masculine and feminine nouns and adjectives (a few exceptions survive today: we say a BLONDE girl but a BLOND boy; we say fox and vixen for a female fox.[8]) Gradually French lost its prestige and popularity with the English ruling class and French though still used in the courts was studied as Latin was as a foreign language. By 1362 English had replaced French as the common language of the English parliament.

FRENCH LOANWORDS IN ENGLISH

| French | English | Commentary/Spanish cognate |

| Chateau-fort | castle | castillo |

| jongleur | juggler | Malabarista; juglar)poet/minstrel is a false cognate |

| prison | prison | prisión |

| service | service | Servicio |

| gouvernment | government | gobierno |

| administration | Administration | administración |

| avocat | attorney | Lawyer/advocate/abogado |

| court | court | corte |

| crime | crime | Replacing the Anglo-Saxon word ‘”sin” Delito ; crimen is MURDER (AS) |

| juge | judge | juez |

| jury | jury | jurado |

| noble | noble | noble |

| royal | royal | real |

| prince | prince | príncipe |

| duc | duke | duque |

| armée | army | ejército |

| capitaine | captain | capitán |

| cabot | corporal | cabo |

| lieutenant | lieutenant | Teniente/alférez |

| sergent | sergeant | sargento |

| soldat | soldier | soldado |

| boeuf | beef | Cow (Anglo-Saxon)vaca |

| mouton | mutton | Sheep (AS) oveja |

| porc | pork | Pig (AS) cerdo |

| veau | veal | Calf (AS) ternero |

| dignité | dignity | dignidad |

| feindre | Feign | fingir |

| fruit | fruit | fruta |

| lettre | letter | Carta (“letras”=words of a song or letters) |

| litérature | literature | literatura |

| magicien;magique | Magician , Magic | AS: Sorcerer/sorcery mago |

| miroir | mirror | AS Looking-glass espejo |

| question | question | Pregunta; cuestión |

| recherche | search | Buscar; investigar |

| secret | secret | secreto |

| son | Sound[9] (noise) | Sound /saludable(AS)=healthy,solid |

| solace | solace | solaz |

| chapitre | chapter | Capítulo |

| dictionnaire | dictionary | AS word-book (diccionario) |

| bestiaux | Cattle (beasties) | Ganado |

| gain | wage | sueldo |

| calibre | Gage (or gauge) | Indicador/calibre |

| garant | Warranty | Garantía (limitada)NOT the same as guarantee.Partially FALSE COGNATE |

| garant | guarantee | Garantía de fábrica |

| mars | March | marzo |

| mélodie | Melody/tune(AS) | melodía |

| Nature/ caractère | nature | Naturaleza/carácter |

| courage | courage | Coraje, valor |

| aventure | Adventure; love affair | aventura |

| spécial | special | Specially part AS especialmente |

| chef | chief | jefe |

| chef | chef | Chef o jefe de cocina |

| champion | champion | campeón |

| Psalmodie/chanter | chant | cantar |

| machine | machine | Note French sound not Greek “K” (máquina) |

| sauvage | savage | Wild (AS) salvaje |

| couleur | Color (colour) | color |

| Honor (honour) | Honor (honour) | honor |

| vertu | virtue | virtud |

| fleur | flower | Flor |

| soupe | soup | sopa |

| Debris; décombres | debris | escombros |

| De luxe | De luxe | De lujo |

| denouement | Denouement or resolution | resolución |

| élite | elite | Elite |

| Hors d’oeuvre | Hors d’oeuvre | Appetizers (tapas) |

| Reveille | Reveille “reVALLEY” in British English | La diana RE-valley in Am. English |

| quitter | To leave (AS) | “to quit” abandonar |

| arrêter | To stop (AS) | “to arrest” ê indicates “s” sound was dropped. arrestar |

| demander | To ask (AS) | “to demand” pedir/demandar |

| penser | To think (AS) | “to be pensive” pensar |

| ami | Friend (AS) | Amicable /amistoso “mon ami” is almost universally known in English just as “mi amigo” |

| pont | Bridge (AS) | Pontoon (temporary Military bridge) puente |

Some mention should be made of “legal doublets” which are common in legal documents and also in cultivated conversation. “Legal doublets” are standardized phrases which we see in wills, legal documents and the Constitution. These expressions are many centuries old and reflect the heritage of common law which knew legal documents in English, Latin and French and a long period of bilingualism in England from the 11th century to the 15th century. Usually a Latin word is paired with a French or Anglo-Saxon word so as to clarify understanding (and probably link to a common law document which could have been recorded in any of the three languages)

| aid and abet | To assist and to encourage Esp. in commission of a crime | (ayudar) |

| Cease and desist (order) | an order of a court or government agency to a person, business or organization to stop an activity is harmful and/or contrary to law. | (orden de la corte para para una actividad) |

| Fit and proper | (apropiado) | Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address “fitting and proper” |

| Full faith and credit | Article IV, Section 1 of the U. S. Constitution which states: “Full faith and credit shall be given in each State to the public acts, records and judicial proceedings of every other state” ( fe y crédito completo) | Thus, a judgment in a lawsuit or a criminal conviction rendered in one state shall be recognized and enforced in any other state, so long as the original judgment was reached by due process of law. ex. Birth certificateHS diplomaDriver’s license |

| Null and void | Nulo y sin valor | Cancelled and having no value (contacts etc.) |

| Sound mind and memory (Mente sana) | having an understanding of one’s actions and reasonable knowledge of one’s family, possessions and surroundings. “ | This is a phrase often included in the introductory paragraph of a will in which the testator (writer of the will) declares that he/she is “of sound mind and memory. |

Many English expressions are direct translations (or calques) of French. For example, if you please (s’il vous plait; RSVP), marriage of convenience (marriage de convenance), that goes without saying (ça va sans dire), reason of state (raison d’etat)), trial balloon (ballon d’essai) even every day expressions like the arm of the professor (le bras d’ professeur rather than the more Anglo-Saxon “the teacher’s arm.” Also we have question de connaissances générales ; general knowledge question ;champion du monde champion of the world (world champion)

Many more French expressions entered the English language in the 16th and 17th century when French was the lingua franca of educated people. Some examples are noblesse oblige (obligation of those of high rank to be generous and noble), de rigueur (required by fashion of custom; wearing a cap and gown at graduation), ancient regime (pre 1789 French monarchy, esprit d’ corps (enthusiasm generated by comradeship and devotion to a cause), vive la difference! (long live the differences between the sexes accepting that men and women and boys and girls will always be a little different from each other). Other French words and expression still very common for educated people are: Femme fatale (woman of seductive charm who leads men into doom), bon mot (witty remark) vis-à-vis (compared to or in relation to) faux pax (false step; social blunder), tour de force (great feat or accomplishment –a goal, a home run a three point play a great book or performance). Milieu (surroundings or environment) , je ne sais quoi (lit. “I don’t know what” –an indefinable elusive quality especially a pleasing one)[10]

[1] In the 19th century Herbert Spencer and others spoke of the “Anglo-Saxon race” but it is certainly more accurate to speak of the Anglo-Celtic or Anglo-British race. The majority of native Britons are at least partially of Celtic origin. English people and British people in general do not look like Germans.

[2] Gilbert Highet, The Classcial Tradition (Oxford, 1949) p. 94.

[3] http://machias.edu/faculty/necastro/chaucer/lgw/ with modern prose translation.

[4] Li romans d’Alixandre (The Romance of Alexander) (c.1170), attributed to clergyman Alexandre de Bernay is based on the translations of various episodes of the conqueror’s life as composed by previous poets ( such as Lambert de Tort)

[5] T. Pyles and J. Algeo, The Origins and Development of the English Language. Harcourt, 1982)

[6] http://itdc.lbcc.edu/cps/english/phonicSounds/index.htm for phonics practice online

[7] Gilbert Highet, The Classical Tradition (1949) p 110.

[8] A vixen is also a woman who is regarded as quarrelsome, shrewish or malicious.

[9] SOUND (1)= healthy (basic Anglo-Saxon word); SOUND (2)=noise (Latin) SOUND 3 body of water, bay (Norse/Viking).

[10] Example: “She may not be especially beautiful , nor very young but she has a certain je ne sais quoi I find irresistible “

CH 2 SHORT HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE

By Richard K. Munro

Chapter two “With God Came Letters and Numbers”

Christianity came relatively late to the pagan Anglo-Saxons of whom it was said, “Neither numbers, nor letters, nor God.” Missionaries from Roman Britain spread Christianity to the Scotti (Gaels) of Ireland and the Picts of Scotland (St. Patrick c 432, St. Columba c. 563 and St. Mungo c 560. for example) thus preserving the ancient faith and knowledge of schooling, books and the Roman alphabet. [1]

In turn, these Celtic missionaries reintroduced Christianity to southern Britain –now known as England- and the Latin alphabet to the Anglo-Saxons. The Irish Gaels were instrumental in this time period in fomenting education and Christianity not only in England but on the continent as well planting an early missionary base on Lindisfarne Island as well as schools in Charlemagne’s empire (present day France, Germany and Switzerland). [2]

Figure 9 THE ROMAN ALPHABET The Latin alphabet originally had 20 letters; the Romans themselves added K plus Y and Z for loan words transcribed from Greek.

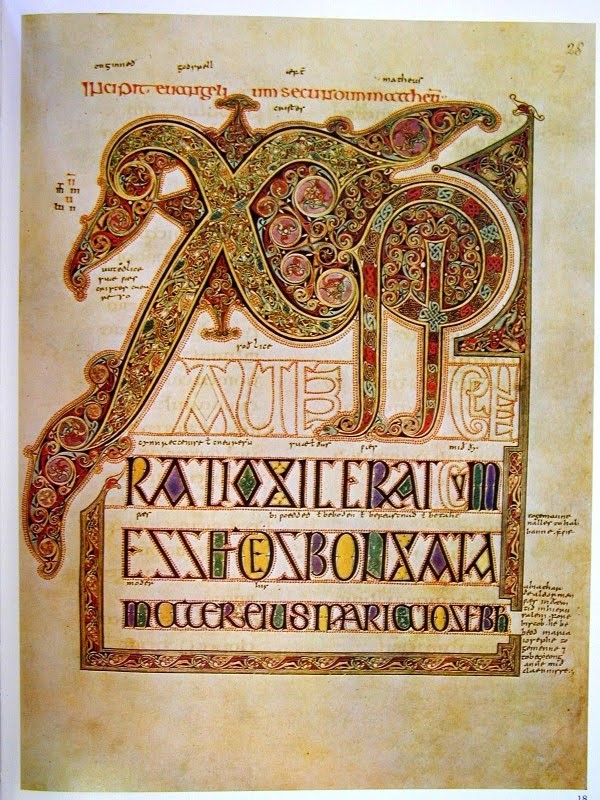

Figure 10 Book of Kells

Another force in Christianizing the Saxons came from Rome beginning with the mission of St.Augustine to Aethelbert, King of Kent, in AD 597. Aethelbert was chosen because he was married to a Frankish Christian princess[3] who encouraged the new religion. The story goes that Aethelbert, afraid of the powers of the Christian “sorcerers”, chose to meet with them in the open air to ensure that they wouldn’t cast a wicked spell over him! In any case, St. Augustine, “the Apostle of the English” laid a solid cultural foundation for English Christianity and the English language.

Augustine’s original intent was to establish an archbishopric in London, but at that time the London English were hard-core pagans, slavers and polygamists and so were very hostile to Christians. Therefore, Canterbury, the capital of the Kentish kingdom of Aethelbert, became the seat of the pre-eminent archbishop in England. The Church was a very important force in medieval English society. It was the only truly national entity –international really- tying together the various warring Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. It is significant to report that no written records of the Anglo-Saxon language survive from before the seventh century AD. The earliest substantial literature of the Anglo-Saxons is Beowulf[4]:

O flower of warriors, beware of that trap.

Choose, dear Béowulf, the better part,

eternal rewards. Do not give way to pride.

For a brief while your strength is in bloom

but it fades quickly; and soon there will follow

illness or the sword to lay you low,

or a sudden fire or a surge of water

or jabbing blade or javelin from the air

or repellent age. Your piercing eye

will dim and darken; and death will arrive,

dear warrior, to sweep you away.”

(translation Seamus Heaney)

If the Anglo-Saxons had remained pagan it is possible that their language may never have been widely written and so may not have survived its many travails.

Figure 11 Lindisarne Gospels

Anglo-Saxon England’s most famous historian and Doctor of the Church , the monk Bede, known as the Venerable Bede, lived most of his life at the monastery of Jarrow, in Northumbria (died 735). Nearby, the monastery of Lindisfarne is famous for its’ celebrated hand-colored illuminated Bible, an 8th century masterpiece of Celtic- inspired art, which is now in the British Library.[5] Lindisfarne Gospels, is a Latin Vulgate text with interlined Old English paraphrase. So it is very important in the history of the English language.

This is evidence that the Masses were given in Latin but the sermons were given (usually) in English. King Alfred’s circle of (Old) English-speaking teachers (Plegmund, Waerferth, Aethelstan, and Werwulf) led to a late 9th century revival of learning in Latin as well as the growth of Anglo-Saxon literature. The Anglo Saxon Chronicle, for example, was written in Old English not Latin). Alfred the Great’s unique importance in the history of English letters came from his conviction that a life without knowledge or reflection was unworthy. Alfred’s enthusiasm to spread learning to the people in English may have been a turning point for the survival of English. Under the auspices of Alfred the Great church schools were encouraged for common people, and many Latin works were translated into English. English was becoming a literary language and a language of local commerce. French was still important for the nobility and Latin for higher education but English soldiers, sailors and merchants continued to speak, to sing and to pray in English among themselves. And, increasingly, keep records and write in English. English became strong enough even to survive the catastrophic subjugation of the English which came after 1066.

Figure 12 Manuscript of Beowulf (Anglo-Saxon)

During this time the influence of Church Latin and St. Jerome’s Latin version of the Bible (known also as the “Vulgate” was colossal. Churches were almost the only forum for higher education[6] during the middle Ages. The higher church officials also played important secular roles; advising the king, witnessing charters, and administering estates of the church, which were extensive. The Magna Charta (1215) was written in Latin and so was the Scottish Arbroath Declaration of 1320. Previously Anglo-Saxon had a few Latin words most of them products or indicating spheres in which the Romans excelled such as road-building, commerce, travel and communication. These early Anglo-Saxon borrowings from Latin or Greco-Latin include, anchor, butter, candle, chalk, cheap[7], cheese, kettle, kitchen, to cook, dish mile, mint, crisp, pepper, port, pound, sack, school (originally Greek) ,shrine, street (paved road), tile and wall. Now with the introduction of a literate Latin Christian culture we have many new words (many originally Greek like the word Bible meaning in Greek “books”)[8] Hundreds of words come into English at this time from Latin and here are just a few: altar, apostle, circle, crystal, monastery, martyr, monk, nun, priest, clerk[9], commandment, devil, demon, relic, cat, fork, creed, mass, camel, psalm, paper, chapter, verse, lily, temple, and trout.

The early monasteries of Northumberland were vital centers of learning and the arts until they were wiped out by savage Viking raids of the 9th century.[10] Much of England, Ireland and Scotland were conquered by the Vikings (c.800-1263) but the Vikings dominated the off shore islands, the sea and the coasts not the hinterland.

![raid[1]](https://spiritofcecilia.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/viking-attack.jpg?w=250)

Figure 13 Viking attack on Christian monastery

The northern dialects of English were very influenced by Old Norse (an ancestor of Norwegian and Swedish but Germanic like Anglo-Saxon). Some examples of Old Norse (Viking) words are fellow, hit, sly, take, skirt, scrub, gill, kindle, kick, get, give, window, skipper, sister, thrall (slave),earl(warrior/noble), want and dream (it meant ‘joy’ in Anglo-Saxon.). [11] Yet despite these sporadic attacks both English and Christianity set deep roots. I cannot but help think that the Vikings were vanquished not only by the sword but by the faith and virtue of young Christian maidens with whom the Norseman cohabited and later married. In time language and religion assimilated and transformed the invader.

[1] After its adoption by the English, this 23-letter Roman alphabet developed W as a doubling of U and later J and V as consonantal variants of I and U. The resultant alphabet of 26 letters has both uppercase, or capital, and lowercase, or small, letters.

English spelling is essentially based on 15th century orthography, but pronunciation has changed considerably since then, especially that of long vowels and diphthongs.

[2] See Thomas Cahill’s charming small book How the Irish Saved Civilization

[3] Named Bertha

[4] Beowulf, Seamus Heaney, trans. ( New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2000)

[5] Older than this are the Book of Kells, its inspiration which was probably created in Iona generations before.

[6] Almost entirely in Latin.

[7] Cheap comes from the Latin caupo meaning “wine-seller”; a Chapman was original a merchant.

[8] Of course, the Anglo-Saxons called the Bible the Gospels, or the Good Book or the Old Book; these are expressions still used in modern English today.

[9] In Britain “clerk” is pronounced like “Clark” as in Clark Kent (Superman); it almost sounds like “clock”.

[10] There was an ancient prayer known round the Isles that went like this: A furore normannorum libera nos domine (“From the fury of the Norsemen deliver us, O Lord!”).

[11] Thomas Pyles and John Algeo The Origins and Development of the English Language Harcourt Brace, 1982 p299-300.

The Monroe Doctrine ~ The Imaginative Conservative

From the perspective of John Quincy Adams, the United States had no right to claim or annex any part of Latin America. It also, however, had no right to deny any part of Latin America from joining its cause with that of the United States.

— Read on theimaginativeconservative.org/2020/05/monroe-doctrine-bradley-birzer.html

Give me not the hard man

I dislike and distrust RUTHLESSNESS, CRUELTY TO THE YOUNG OR WEAK, COLDNESS to our neighbors and loved ones, INDIFFERENCE to the old, sick or poor, HARD-HEARTEDNESS and INSENSITIVITY.

Give me a person who is of a softer heart and open ear. Nil am fear crua gan croí báúil nó cluaise (not the hard man without a sympathetic heart or ear).

What is sympathy? It is an emotional participation in the feelings of others and let us not forget there is a pleasure to be found and a appeal as a result of those feelings.

Compassion is the opposite of cruelty which rejoices in the suffering and humiliation of others and egoism which is indifferent to the suffering and humiliation of others. Hasta los pobres tiene derecho al honor y dignidad as the Spanish say; even the poor have the right to honor and dignity.

I believe men and women who…

View original post 60 more words

Give me not the hard man

I dislike and distrust RUTHLESSNESS, CRUELTY TO THE YOUNG OR WEAK, COLDNESS to our neighbors and loved ones, INDIFFERENCE to the old, sick or poor, HARD-HEARTEDNESS and INSENSITIVITY.

Give me a person who is of a softer heart and open ear. Nil am fear crua gan croí báúil nó cluaise (not the hard man without a sympathetic heart or ear).

What is sympathy? It is an emotional participation in the feelings of others and let us not forget there is a pleasure to be found and a appeal as a result of those feelings.

Compassion is the opposite of cruelty which rejoices in the suffering and humiliation of others and egoism which is indifferent to the suffering and humiliation of others. Hasta los pobres tiene derecho al honor y dignidad as the Spanish say; even the poor have the right to honor and dignity.

I believe men and women who do not know mercy miss much of the joy and happiness to be found in life.

There is sadness in pity -commiseration- but there is happiness mingled together with compassion whose example generates generosity and love from others.

Sadness devoid of hatred for anything but injustice and unhappiness and suffering is a good thing, a humane thing.

RICHARD K. MUNRO

Russell Kirk on Equality, 1963

Really, men are equal in two ways only: before the judgment-seat of God (who, remember, doesn’t assign them all to the same place), and in the eyes of the law. But human beings are not equal otherwise; and because they are unequal, they are not entitled to identical things. Every man is entitled to what is his own; but he has no right to take away from another who has more by his talents or inheritance.

For the slothful man is not equal to the diligent man. The brute is not equal to the saint. The fool is not equal to the sage. The traitor is not equal to the loyal man. The selfish is not equal to the loving. The coward is not equal to the hero. The rogue is not equal to the just judge. And nothing could be more unjust than to treat all these, under the lunatic pretext of natural equality, as if they ought to live one life and enjoy the same rewards.

—Russell Kirk, CONFESSIONS OF A BOHEMIAN TORY, 1963, pg. 280.

Upon losing a beloved father

Thomas Munro Jr.

By RIchard K. Munro

The ladies to my father’s left are my mother, Ruth L. Munro and in the back Juanita Donado Perez my beloved mother in law. A grand lady and like my grandmother lost her husband when very young (at age 26). My wife was like my mother “the widow’s curly haired daughter who was the loveliest of the throng.”

I know what it is to love a father and to lose a father.

“Death leaves a heartache no one can heal, love leaves a memory no one can steal.” is an old Irish saying.

NE OBLIVISCARIS..DO NOT FORGET.

People you love never die entirely. They live in your mind in, the way…

View original post 2,556 more words

Dylan thomas, Gifted and tortured poet

An Ontario Tempest

The next Shakespeare@Stratford film to hit YouTube is the Festival’s 2018 production of The Tempest, premiering on Thursday, May 14 and running for three weeks. Here’s my review from when my wife and I saw the play live in October of that year.

This is the third production of The Tempest we’ve seen at Stratford, Ontario; since we started attending in 2004, the Festival has usually marketed the play as a chance to catch an actor of high skill and reputation (and often getting on in years) in the role of Prospero. 2005’s Tempest served as a grand farewell for William Hutt, the most accomplished classical actor in Canada’s theatrical history; the 2010 production was built on Christopher Plummer returning to the scene of his earliest triumphs. This time around, the hook was seeing Martha Henry (since Hutt’s passing, the current Greatest Living Canadian Actor) playing the exiled magician — part of a season with multiple productions (a gender-swapped Julius Caesar and a gender-fluid Comedy of Errors, along with the drag-rock musical The Rocky Horror Show) trendily exploring postmodern conceptions of freedom.

But any dreams or fears of a transgressive Tempest faded quickly; Henry forthrightly played Prospero as female — duchess of Milan, mother of Miranda, wizard ruler of an uncharted, enchanted island — with a few modest tweaks of the script not even scuffing the verse rhythms, and that was that. (After all, it’s a fairy tale; if you’re worried about the lines of descent for Renaissance Italian nobility being messed up, you’ve come to the wrong play.) Even better, this was an ensemble Tempest, with Henry clearly featured, but also clearly first among equals. Rather than chewing scenery a la Plummer or waxing grandiloquent like Hutt, she drove the plot without swallowing the stage, working to provide for her daughter, bring those who exiled her to book, reward virtue and punish wrong with formidable focus, aplomb and dry humor. And all the while, she genuinely wrestled with conflicting impulses: would she take vengeance on her adversaries, or show them mercy? It’s a tribute to Henry’s and director Antoni Cimolino’s conception that, even if you knew the play, the answer wasn’t telegraphed.

The strong cast also elevated this production, consistently playing off Henry’s indispensable work while fruitfully developing their own characters. Andre Morin’s Ariel did Prospero’s bidding with delight, while holding her to the promise of eventual freedom; Michael Blake’s Caliban chafed convincingly under her authoritarian rule. For once, the shipwrecked mariners were three-dimensional characters, not plot tokens — the King of Naples Alonso (David Collins) ripely autocratic, Prospero’s usurping brother Antonio (Graham Abbey) convincingly sociopathic, counselor Gonzalo (Rod Beattie) more of a sage and less of a fool than usual. Tom McCamus as butler Stephano and Stephen Ouimette as jester Trinculo clowned to perfection, nailing every laugh possible whether on their own, with Caliban or with the ensemble. The young lovers were the most pleasant surprise; Ferdinand and Miranda can feel like weak sauce in the wrong hands, but Sebastien Heins & Mamie Zwettler were spunky, passionate, intelligent, fully cognizant of their developing affections — strong & spot-on.

And yes, the special effects and pageantry (serious creature puppetry by the ensemble of Spirits & Monsters at key moments, Festival stalwarts Chick Reid and Lucy Peacock regally presiding over Act Four’s celebratory wedding masque) were impressive as always. But Stratford productions go deepest when they cut to the heart — and this Tempest showed us, beyond its numerous charms and delights, the depth of Prospero’s sacrifice. To become truly great as well as truly free, the exiled ruler must serve her enemies as well as her friends — forgiving wrongs, securing Naples and Milan’s future through Ferdinand and Miranda’s marriage, releasing the spirits of the island, and abjuring her “rough magic.” Martha Henry’s reading of Shakespeare’s Epilogue – bereft but relieved, slyly humorous in its appeal to the audience for final release through prayer and applause – communicated both the cost of Prospero’s renunciations, and their true worth. It was a lovely end to the best, most bracing production of The Tempest we’ve seen at the Festival.

Watch the premiere of The Tempest on the Stratford Festival’s YouTube channel tomorrow at 7 pm EDT; a pre-show chat with Martha Henry, Mamie Zwettler and Antoni Cimilono starts at 6:30 pm.

— Rick Krueger

You must be logged in to post a comment.