At first glance, Elora is a typical tourist-oriented village in Ontario’s Golden Horseshoe. Its town center sweeps downhill toward a historic mill on the Grand River, now the focus of redevelopment via a luxury hotel/spa complex. It boasts plenty of chichi boutiques, upscale brewpubs and posters about upcoming weekend festivals. A well-stocked local grocery store and the inevitable Shoppers Drug Mart speaks to the place’s practical streak; two enticing bookshops (one stocking new releases, one second-hand treasures) testify that food for the mind and soul are on the menu as well.

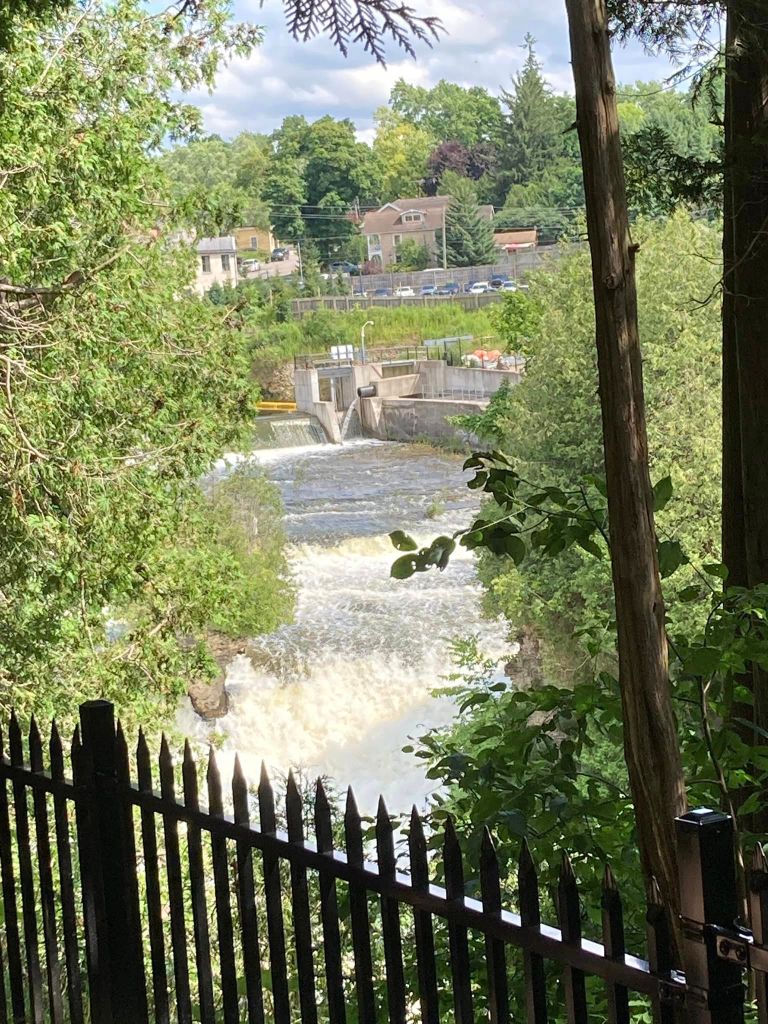

But taking the high concentration of limestone buildings in Elora as a clue reveals the true heart of its attraction. Just west of downtown, the Elora Gorge lies downstream from a 25-foot waterfall, its 72-foot cliffs towering over the path of the Grand for more than a mile. Whether viewing it from the village’s pedestrian footbridge, the elevated trails that wind through and around it, or down at the riverbank itself, the cliffs and crannies quickly bring the word sublime to mind.

Why? The Oxford English Dictionary definition states the substance of the sublime nicely:

Of a feature of nature or art: that fills the mind with a sense of overwhelming grandeur or irresistible power; that inspires awe, great reverence, or other high emotion, by reason of its beauty, vastness, or grandeur.

And that experience chimed perfectly with our day’s next activity – the final Choral Evensong of this year’s Elora Festival, held at the Church of St. John the Evangelist, less than two blocks from the Gorge. The past lies thick within St. John’s walls (constructed in 1875), from the communion set that Florence Nightingale donated to the parish’s first priest (on display behind the organ console) to what a church brochure calls its “strong history of liturgical worship and choral music.”

Led musically by the 21-strong Elora Singers, conductor Mark Vuorinen and guest organist Christopher Dawes, this Evensong unfolded in classic fashion: a long-established liturgical structure augmented with appointed hymns, psalms, readings and prayers. From the opening words of the ancient chant “To You, Before the Close of Day”, the congregation joined in with heart and voice as the choir processed to its stalls; the core texts of Confession, Creed and Lord’s Prayer were spoken with vigor and affection; a whimsical homily on Matthew 26 sharpened to a serious point, tracking remarkably well with Timothy Dudley-Smith’s hymn text on our daily callings “How Clear Is Our Vocation, Lord” (the text itself set to a robust tune by arch-British composer Charles Parry).

And throughout the service, we were given multiple tastes of the musical sublime, starting when Dawes’ rendition of Herbert Howells’ Psalm Prelude based on Psalm 33:3 (“Sing to Him a new song; play skillfully with a loud noise”) roared to life, filling the sanctuary with arresting, rhapsodic melody, thick, juicy chords and supple, flexible rhythms. Howells’ Evening Canticles for King’s College, Cambridge unfurled in similar romantic fashion, the Singers proving exquisitely sensitive to the musical and textual nuances. To quote the composer, in this Magnificat a humble Mary exalted her Son while the mighty were “put down from their seat without a brute force which would deny this canticle’s feminine association”; the Nunc Dimittis’ tenor solo (beautifully voiced by Singer Nicholas Nicolaidis) perfectly “characterize(d) the gentle Simeon” as he held the Christ Child and thanked God for His promised deliverance. So when the chorus and organ ramped up on each canticle’s concluding “Glory be to the Father”, the weight of praise seemed to encompass not just those in attendance, but the whole of creation, landing on “world without end, Amen” with breathtaking depth, substance and impact. But there was more!

Welsh composer William Mathias’ contrasting musical language –cheerful, quicksilver, rooted in a rumbustious sense of the dance — proved equally riveting on the anthem “Let the People Praise Thee, O God” (composed for the wedding of Prince Charles & Lady Diana Spencer and sung with joyous, sympathetic precision) and a closing organ Recessional so vivacious that it set toes tapping, even as the instrument’s festival trumpet echoed around, tumbling down scales like water streaming down the Gorge. It proved an exhilarating coda to the final hymn, “The Day Thou Gavest, Lord, Has Ended”. As John Ellerton’s stirring invocation of God’s presence in creation and the Church unrolled to Clement Schoefield’s majestic melody, the Elora Singers filled the center aisle with rich harmony and a soaring soprano descant to cap a worship service like few others I’ve experienced in my life.

In his new book Cosmic Connections: Poetry in the Age of Disenchantment, Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor explores the roots of what he calls “a language of insight”, a way of exploring “phenomena like value, morality, ethics and the love of art itself” beyond the reductive terms of mechanistic natural science that frame so much of our daily lives. I consider it a gift to have, on the same day, explored the language of Nature and the language of faith, in each instance pulled by the sublime toward a deeper connection with what has been before I was born and, Lord willing, what will continue beyond the hour of my death.

— Rick Krueger

You must be logged in to post a comment.