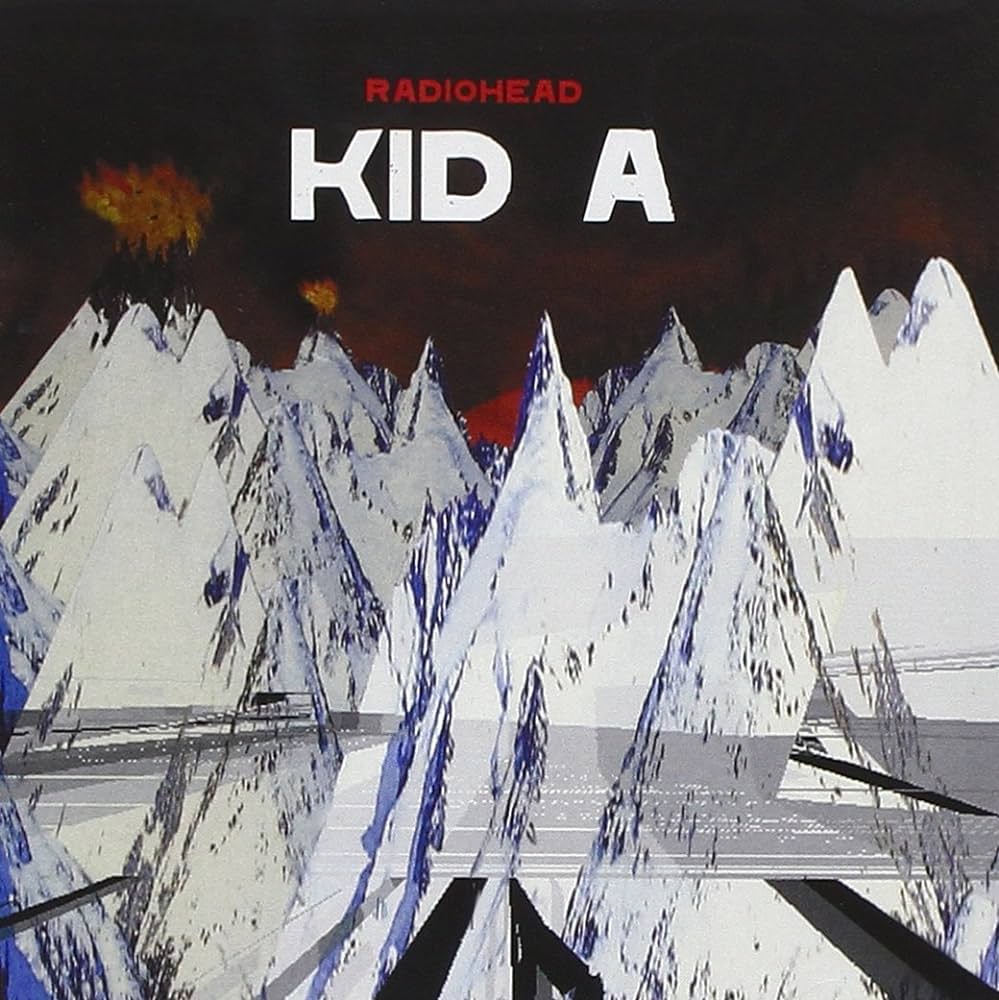

Dear Spirit of Cecilia readers, it’s time to dig into some prog/anti-prog/a-prog. Is Radiohead prog or not? I’m sure this question has been debated before. Let’s just say, Radiohead did something unique and did something unique several times. First, with Ok, Computer in 1997 and, then, again, in 2000 with Kid A. The following dialogue reflects our thoughts about such innovation and creativity in the world.

Brad: Well, I’m happy to begin this conversation. In the mid 1990s, I had heard the single, “Creep.” Strangely, I was more familiar with the live Tears for Fears cover version than I was with Radiohead’s original, but I still knew the song pretty well. To this day, I like the song, but I don’t love it. And, if push comes to shove, I prefer the TFF version. The unedited, R-rated Radiohead version of the song does nothing for me.

The mid-1990s were kind of wild for me, in terms of my profession as well as in my life. I didn’t get married until 1998, when I was 30. For part of the mid 1990s, then (single), I was working in Bloomington, Indiana, while working on my PHD (I loved Bloomington and my job there), and, for part of it, I was working in Helena, Montana (a city I loved, in a job that I hated; well, let me clarify. I was working at the Montana Historical Society which I hated, but I was also teaching at Carroll College, which I loved).

One day in Helena, I went to a local alternative shop (comics, music, etc.) to buy the latest issue of The Batman Chronicles. On display, though, they had OK Computer, advertised as a “neo prog classic.” Despite money being tight, I bought the album, went back to my apartment, and was suitably blown away by it. Though I love Kid A more, I still have great fondness for Ok, Computer and always will. Though “Karma Police” was the big single from the album, it’s the beginning of “Subterranean Homesick Alien” that I love the most.

From there, I went back and bought the first two Radiohead albums–Pablo Honey and The Bends. I also bought the two eps–by special order–My Iron Lung and Airbag. For what it’s worth, it was the two non-prog songs from the early albums–”Blowout” and “Street Spirit” that most intrigued me.

Tad: Brad, thanks for kickstarting this conversation about two albums that I like a lot. I got into Radiohead around the time of The Bends. I thought that record was wonderful, because I have always had a soft spot for Beatlesque power pop. I didn’t really enjoy OK Computer, because I felt that they had betrayed their pop roots! Of course, with the passage of time and greater perspective, I love it now (except for Fitter, Happier).

When Kid A was about to be released, I remember they put out Everything In Its Right Place as a teaser on Amazon, I think (this was years before YouTube, remember!). I listened to that one track obsessively – I couldn’t get enough of it! But when the entire album was finally released and I got a chance to listen to it, I was completely turned off. To my ears, they had completely abandoned melody and replaced it with abrasive noise. It was literally years before I would return to it and give it another chance.

I guess I have a love/hate relationship with Radiohead. I spent the past couple of days listening to Kid A and Amnesiac (along with the bonus tracks on their 2009 respective reissued editions). There are moments of incredible beauty on both albums: Everything In Its Right Place, Optimistic, Pyramid Song, Knives Out, come to mind. But Thom Yorke’s vocals grate on me in so many places. He sounds querulous and whiny; it’s as if he can’t find any joy in life at all. “Catch the mouse/crush its head/throw it in the pot”…. Is that a rant against meat eaters? I don’t know, but he sounds so desperate!

Also, Stanley Donwood’s artwork is extremely off putting to me. There is a condescension and disdain for normal people who are just trying to raise a family, earn an honest living, and not make waves. Maybe I’m reading too much into it, though. Tell me where I’m wrong, please!

Brad: Tad, thanks so much for your good thoughts. You and I almost always agree, so it’s really interesting to me when we diverge from one another. My views are almost completely opposite of yours, but I suppose timing has a lot to do with it. I mentioned earlier that I came across OK Computer really by chance – seeing it in a display in an alternative shop in Helena, Montana, of all places.

I was in my second year at Hillsdale when Kid A came out. It was the fall semester, and I remember so clearly getting the album. I not only played Kid A repeatedly, but I poured over the lyrics, the art, the booklet, anything that would offer even a smidgen more information about the band and the album. I absolutely loved it when I discovered there was a second booklet, locked under the cd tray.

I played Kid A so much–especially in the background during office hours–that it became a conversation piece with my students and me. So, the album is associated–for me at least–with extremely good memories.

And, I actually like Donwood’s artwork. I even own two books of his art, one of which I have proudly displayed on our living room bookshelf!

Carl: I know, for a fact, that I cannot be objective at all about either album! And there is some freedom in admitting that.

I can relate quite well, Tad, to two of your remarks: the one about having a “love/hate relationship with Radiohead” and your observation that “there are moments of incredible beauty on both albums…” Amen, amen!

For me, setting aside “Fitter, Happier,” which is either an act of genius or an act of cynical annoyance, I think OK Computer is one of the most beautiful, gut-wrenching albums ever recorded—regardless of genre. I don’t recall Radiohead being on my radar at all back in 1997, when I walked into CD World (R.I.P.) in Eugene, OR, and heard it on a listening station.

I was immediately transfixed by the album, which I bought and then listened to hundreds (no exaggerations) of times over the next couple of years. I would listen to it often while driving to and from Portland, from the fall of 1997 to spring of 2000, for MTS classes.

Oddly enough, the stark—but somewhat hopeful—lyrics seemed to go well with my studies, although I don’t know how to explain it. But, again, it was the sheer gorgeous quality of the album, with its amazing melodies, detailed arrangements, astonishing sonics, and the elastic voice of Thom Yorke. And the guitars! I soon bought both Pablo Honey and The Bends, and while the debut album was “okay,” I thought the sophomore release was a remarkable work, with several songs that rivaled what came along on OK Computer.

I mention the guitars because my first reaction to Kid A was simply, “What the hell is this?! Where are the guitars?!” It threw me for a loop so deep and big that I actually refused to listen to it for quite some time. For whatever reason, it did not connect with me at all.

Oddly enough, it was through some acoustic/instrumental covers of Radiohead songs—by pianists including Christopher O’Riley, Brad Mehldau, and Eldar Djangirov—that I warmed up to the album. And while it will never, for me, equal its predecessor, I now recognize just how great it is. Once again, it’s the beauty of the music—in songs such as “Morning Bell”, “Everything In Its Right Place”, and “How To Disappear Completely”—that comes to the fore.

Tad: Carl, you expressed my initial misgivings about Kid A so much better than I did. “Where are the guitars?” Yes!!! I also gained a greater appreciation for the songs on Kid A, composition-wise, through listening to Christopher O’Riley’s classical piano versions. I love the album now. As far as Donwood’s artwork, I just get such negativity from it, but that’s my personal reaction.

Looking back, it’s hard to understand these days just how influential Radiohead was. Everyone was compared to them. I don’t think there would be a Coldplay without Radiohead. Remember the British band Travis? They were a poppy, “safe” version of Radiohead. One of my favorite European groups is Kent, from Sweden. They were obviously heavily influenced by Radiohead.

What is amazing to me is how Radiohead kept their audience, no matter how left-field and out-there their music got. I also appreciate how innovative they were in marketing themselves. Remember when they released In Rainbows online, for basically free? They anticipated streaming music years before it existed.

Brad, I wish I had the same experience you had of stumbling across OK Computer and incorporating Radiohead’s music into your life. I think I feel the same way about earlier artists such Roxy Music, Depeche Mode, and New Order. I can’t imagine not having them available, and their music means so much to me on an emotional level. Listening to them still transports me to different times of my life.

Kevin: The confluence of artists assembled in the conglomerate called Radiohead is remarkable. It is rare for a musical group to emerge that gels together. It is yet rarer for one to collectively seek something new and striking, something visionary. It is the rarest of all to have one that can consistently break new territory in a way that feels always new.

In the summer of 1997, having just completed a recital and performer diploma in classical guitar, I began work on my second progressive rock album. I was seeking to break such new ground working on compositions, lyrics, instrumentation, arrangements. It was a joy and yet painful to continually do this work on my own while seeking sympathetic artists to this vision. In particular I was seeking a drummer who could capture the raw talent of my original co-conspiriator, my brother Colin.

Colin and I had literally grown together in our listening, writing, and performer during my latter school days at home. We didn’t need conversation to know when things worked—we just clicked. I didn’t realize just how rare this was until some years later when we did find a chance to regroup and perform again.

In 1997 we were thousands of miles apart and still living in the days when long-distance calls were as rare as they were expensive. But during one such rare call, I remember him mentioning that I had to get the new Radiohead album OK Computer. He knew my tastes. He knew my aversion to new music of the 90s—for the most part I found grunge to be over-blown and entitled. There were exceptions, but it all seemed unjustifiably angry and sulking and focused on screaming in the darkness because they couldn’t be bothered to look for the light switch.

OK Computer, he assured me, was “different. You have to give it a listen!”

The opening distorted guitar line of “Airbag” gripped my attention immediately. It was melodic but angular, technically adept but rough at the edges, weirdly familiar yet strangely weird. One thing was abundantly clear—these guys had it. The playing was exciting, inventive, and in-the-pocket— except when the haunting character android made its presence felt—and then it was oddly off-kilter, but consistently the band worked its magic together, as a multiple pulsing organism.

The album is brilliant and it set a new standard for creativity in the popular music realm. I could write a book on this album alone. Their use of texture, tone, timing, timbre, text, and contrast appears to flow effortlessly from their collective creative pen. These skills fully come to the fore on OK Computer, where there is a loose narrative (dare I say “Concept”) to the album. But equally on Kid A the stops and starts within and between tracks, the intros and endings, the attentiveness to sonic space. Historically there are moments of brilliance throughout the progressive rock catalog, but here, in Radiohead, was something for a new millennium. Even the contrast between OK Computer and Kid A is extraordinary.

Then there are the melodic and harmonic moments of sheer genius! The way the melodies weave from one section to another, the shift of harmonic focus from a single altered note, the blurring of lines between keys and major/minor constructions. You all know my fondness for Talk Talk’s latter work, which expresses through minimal chords and melodies and achieves artistic triumphs using very basic musical theorems combined with an incredible musical instinct. Radiohead uses maximalism in their approach and since it is a vision more of a collective than a single artist, the result is almost overwhelming to the senses. After a good listen to either of the albums of this essay I literally have to give my ears a rest—it’s so intense.

And yet, listening back, while I still love the creativity, the craft, the brilliance, the technical adeptness, I have to agree with Tad. The dark vision and tone and word with no hint of redemption anywhere suffocates. It’s one thing to work with chiaroscuro, the renaissance artistic technique of using darkness to emphasize the light. Radiohead accels at contrast from a sonic standpoint. I just wish the texts and the vision equally offered an understanding of the beauty of life and not only its tensions. I love the experience of Radiohead’s extraordinary works of human imagination, but in the end I crave the light.

Brad: All right, friends and neighbors, this concludes our discussion of Radiohead–and not just Radiohead, but classic Radiohead–OK Computer and Kid A. As is obvious, we don’t all agree, but we love one another! Here’s hoping you love us as well.

As always, we recommend you buy from Burning Shed, our go-to online store: https://burningshed.com/product/search&sort=p.viewed&order=DESC&filter_tag=Radiohead

You must be logged in to post a comment.