I thought there were three genuinely great things about the Tony Award-winning musical Something Rotten, as currently playing at the Stratford Festival:

1. Mark Uhre’s frenetic take on struggling Elizabethean playwright Nick Bottom. Between his oversized desire for fame, his strained interactions with enterprising wife Bea (a confident Starr Dominque) and poetic little brother Nigel (Henry Firmston in the boy-next-door role), and his obsessive drive to take down William Shakespeare and win the Renaissance fame game, Nick is desperation personified, thoroughly uncomfortable in his own skin and all the funnier for it. Uhre plays him as a live-action version of Daffy Duck, spluttering with unbounded rage at his situation, and thus completely susceptible to any bizarre idea that crosses his path – like inventing the musical – and thus totally willing, no matter how insane the consequences that follow, to “commit to the bit”.

2. The thing is, in this universe, Nick’s right! Framing Shakespeare as a vain, manipulative rock star (continuing the parallel, think Bugs Bunny without redeeming qualities) is Something Rotten’s masterstroke. Trailed by his own theme song and a crew of dancing Bard Boys, basking in the adulation of a solo stadium gig (with hilariously low-tech special effects), scheming against Nick to the point of donning a fatsuit disguise and a Northern accent, stealing Nigel’s best lines and passing them off as his own, Jeff Lillico is a utter hoot, England’s greatest dramatist as an egotistical, over-the-top pantomime villain. Even when he lets his guard down in his big solo “Hard to Be the Bard”(“I know writing made me famous, but being famous is just so much more fun”) , this is a Shakespeare you can love to hate.

3. Speaking of over-the-top, director Donna Feore and her creative team absolutely chose the right path by leaning into the Broadway musical’s inherent absurdities, as foreseen by cut-rate soothsayer Nostradamus (Festival veteran Dan Chameroy in a giddy, disheveled supporting turn):

You could go see a musical

A musical

A puppy piece, releasing all your blues-ical

Where crude is cool

A catchy tune

And limber-legged ladies thrill you ’til you swoon

Oohs, ahhs, big applause, and a standing ovation

The future is bright

If you could just write a musical

Every possible cliché you can think of is there onstage for those six minutes: Sung recitatives (with self-mocking asides)! Bawdy double-entendres and suggestive choreography! Costume changes (including nonsensical hats and wigs)! Jazz hands! Synchronized high-kicking (with callbacks goofing on Feore’s 2016 Festival production of A Chorus Line)! It all worked to perfection at this matinee, the capacity audience (including your scribe) yelling and applauding for more (which the company obligingly provided) as if Pavlov had just rung his biggest, shiniest bell. And the places Nick and Nostradamus find themselves going in the second act’s big number scale even zanier heights. Complete the sentence yourself: “When life gives you eggs . . .” Then imagine the costumes!

Where Something Rotten falls short? Compared to the sublime ridiculousness of the main story, the supporting characters’ arcs bog down in vapid sentimentality and already-stale contemporary memes. Bea’s occasional empowerment shoutouts pale in comparison to what she actually does out of love for her husband and his brother, subtly undercutting her role as the true hero of the piece. Nigel’s emergence from Nick’s shadow is a bit of a damp squib; his main solo turn “To Thine Own Self Be True” proves an shallow, unearned manifesto of self-actualization instead of a rite of passage. And the meet-cute romance between Nigel and Portia (Olivia Sinclair-Brisbane, winningly portraying a budding poetry fangirl under the thumb of Juan Chioran, a Puritan father given to pre-Freudian slips) sputters, toggling between aren’t-we-transgressive smuttiness and, in “We See the Light”, a Big Message about tolerance, tediously staged as a clumsy cross between Sister Act and Rent — Feore’s only directorial misfire.

But that said, Something Rotten’s full-on commitment to farce and totally bonkers energy (with Feore, Uhre, Lillico and Chameroy setting the pace for a young, frisky cast) carries the day. Productions about Shakespeare at the Stratford Festival are typically on or about at the same level as their productions of Shakespeare, and this delightfully nutty escape into a toe-tapping alternate version of the Renaissance is no exception.

— Rick Krueger

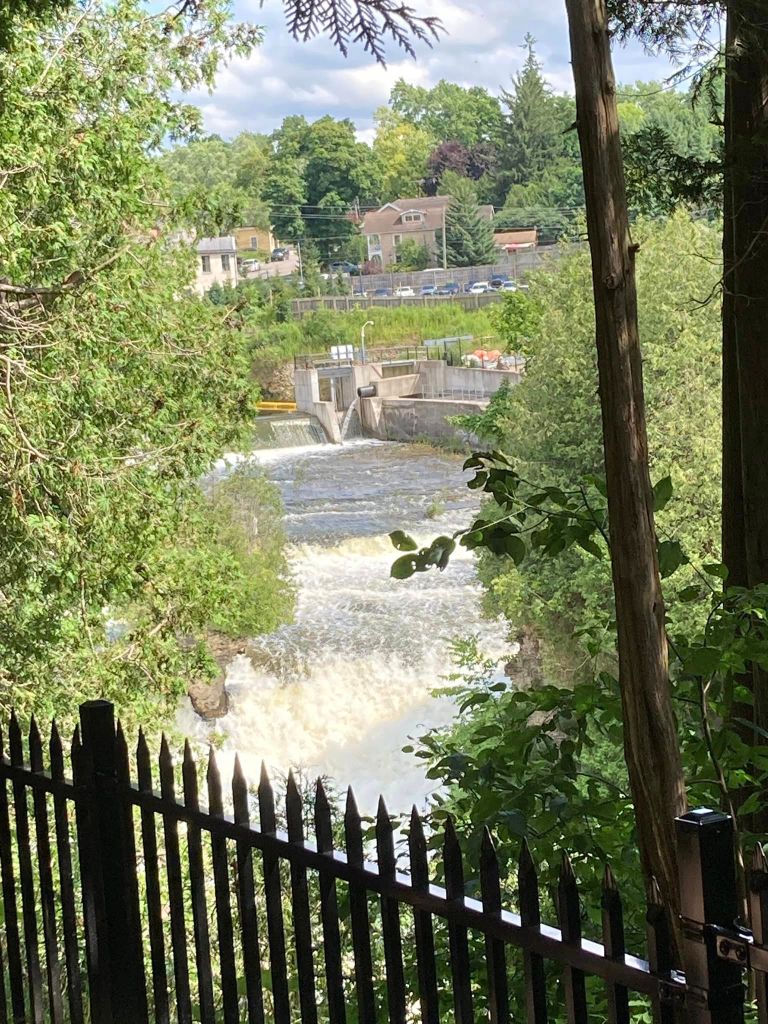

Something Rotten continues at Stratford Festival’s Theatre, with its run now extended through November 17th. Click here for ticket availability.

You must be logged in to post a comment.