(Please note that links to online listening are included below, usually in the album title!)

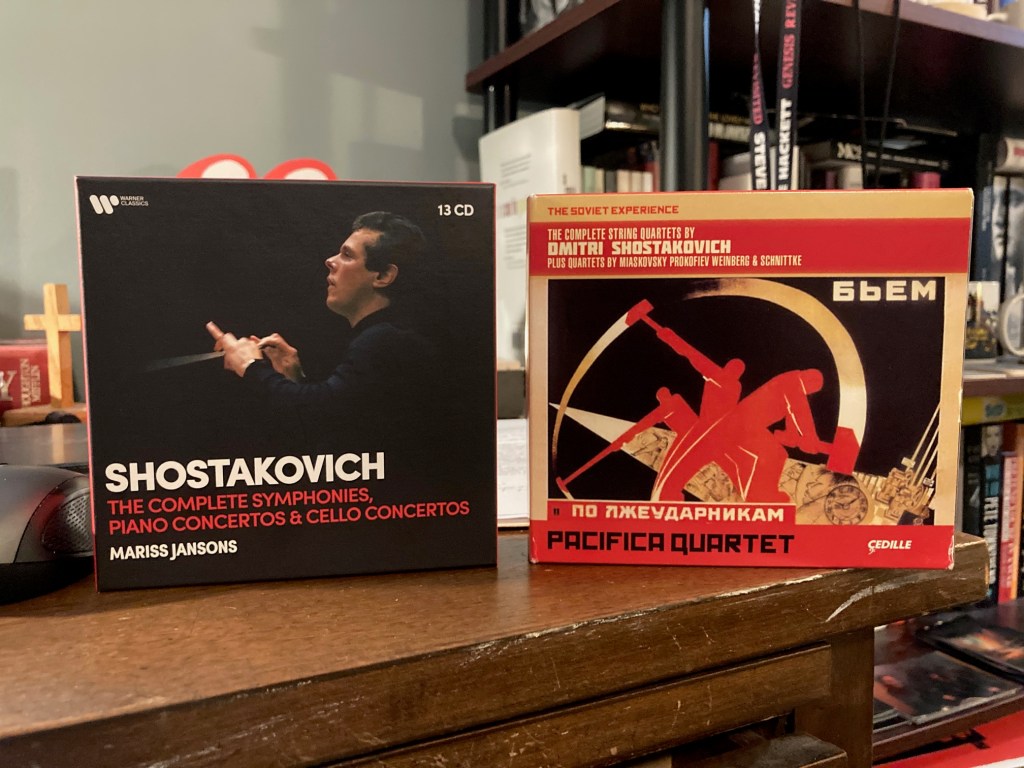

I spent a good chunk of this year digging into the music of Dmitri Shostakovich (2025 was the 50th anniversary of his death). Living in Soviet Russia under Stalin’s iron regime, Shostakovich’s modernistic compositions faced unending attack from jealous rivals and government bureaucrats; public dissent would have been futile, resulting in imprisonment or death for himself and his loved ones. So his 15 symphonies (conducted by Latvian maestro Mariss Jansons in a splendid bargain reissue) walk a thin line between deadpan conformity laced with mocking undertones (#2 “The Fifth of May”, #11 “The Year 1905” and even #5, his most popular work) and striking outbursts of grief in the wake of World War II’s human costs (#7 “Leningrad”, #13 “Babi Yar”). Meanwhile, Shostakovich’s 15 string quartets, composed “for the desk drawer”, were where he let himself go, taking his tragic/satiric outlook to agonized, bleak extremes. In The Soviet Experience, an engrossing bargain box on Chicago’s Cedille label, The Pacifica Quartet (currently resident at Indiana University) provide forceful, rhapsodic performances of Shostakovich’s early quartets #1-4, the expressive, moving #5-8 and #9-12, and the ghostly, late #13-15, plus selected, comparable quartets by Russian contemporaries. If Shostakovich’s music sounds intriguing to you, either of these sets would be excellent ways to gain your footing for further exploration.

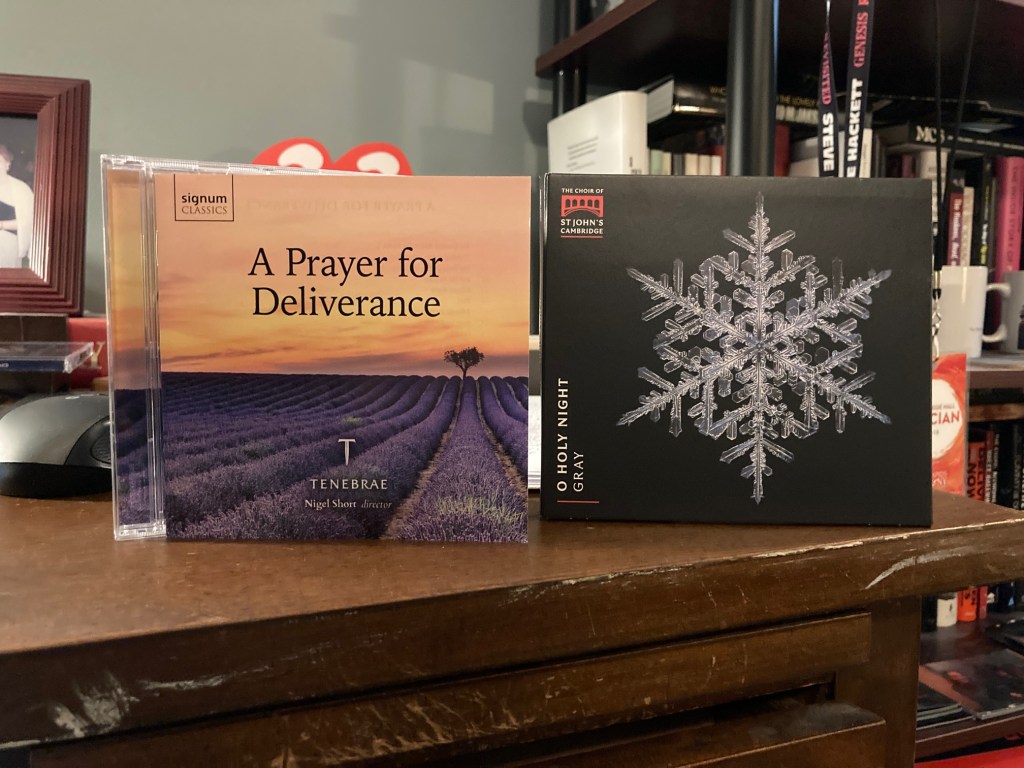

While my most memorable live classical experiences this year (first in Chicago, then in Cleveland) were orchestral, my favorite classical recording was choral: A Prayer for Deliverance, recorded live by the British choir Tenebrae under the direction of Nigel Short. Organized around rich, resonant settings of the Psalms and other texts of mourning and memorial, the program spans two centuries of music and a vast swath of feeling, from the brand-new title work (an anguished interpretation of Psalm 13 by African-American composer Joel Thompson) to Herbert Howells’ peacefully luminous Requiem (incorporating Psalms 23 & 121). It’s a powerful journey from the shock of death to the peace of acceptance — and the hope of resurrection. And since I was privileged to hear the choir of St. John’s College Cambridge when their US tour came to Grand Rapids last spring, I can heartily recommend their fine new Christmas disc O Holy Night (the first spearheaded by the choir’s current director Christopher Gray), centered on Howells’ lush and gorgeous Three Carol-Anthems and Francis Poulenc’s solemnly beautiful Christmas Motets.

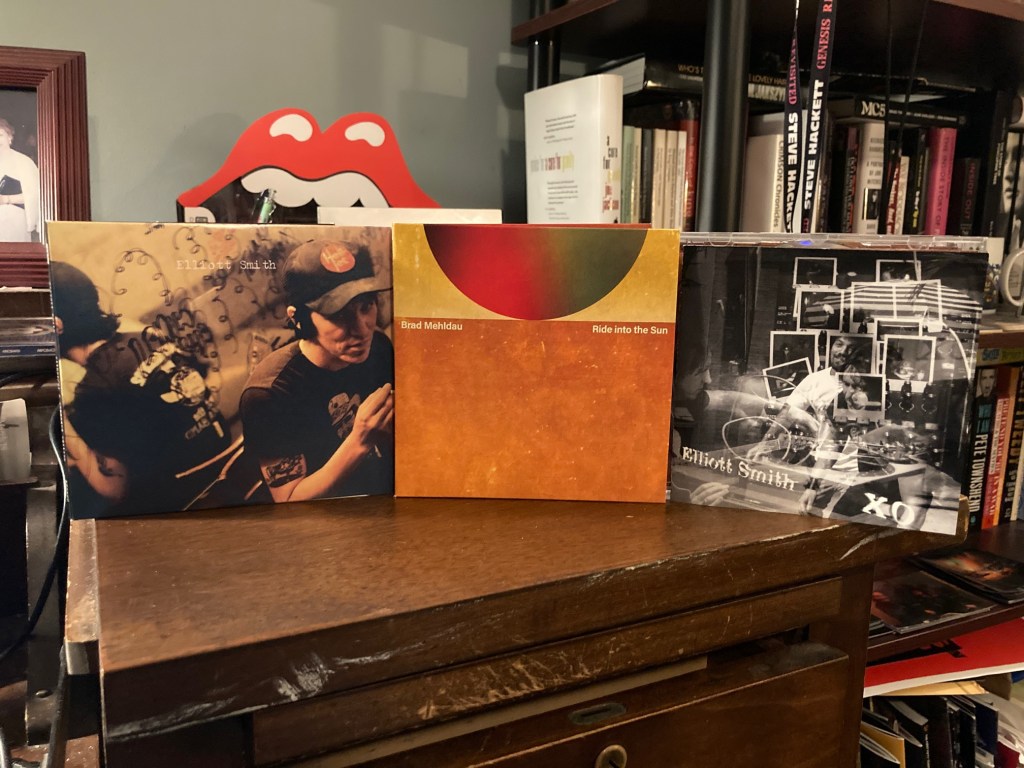

Moving to jazz, my favorite disc of the year has to be pianist Brad Mehldau’s deep dive into the songs of acoustic-grunge cult figure Elliott Smith, Ride into the Sun. Laying down a marker in his eloquent liner notes, Mehldau describes Smith’s work as “sublime music that holds a mirror to our sadness and breathes beauty and meaning into it”. And from a breath-snatching opening take on “Better Be Quiet Now” to the serene two-part title track (plus side quests into similar cult faves Big Star and Nick Drake), Mehldau and his numerous guests prove the point again and again; steeped in late Romantic harmonies and subtly swinging all the while, they unerringly steer Smith’s melodies through the heart of darkness to the sweet consolations of art reflecting on that pain. (Want to hear Smith’s originals? I highly recommend his 1997 indie release Either/Or, where you can hear him straining at the expressive limits of low-fi, and his 1998 major label debut XO, where he unleashes his inner McCartney/Brian Wilson in a dizzying display of studio shock and awe.)

But I have to say that Somni, the latest live collaboration between jazz-fusion big band Snarky Puppy and The Netherlands’ Metropole Orkest isn’t far behind Mehldau’s tribute to Smith. A more noir take on the filmic funk of previous collaboration Sylva (reissued last year, alongside the Puppy’s most popular live-in-studio recording We Like It Here), there’s an embarrassment of riches here, with band and orchestra deployed like interweaving chamber groups, ear-catching fades and dissolves between themes, scorching virtuoso solos on every track, and an endless variety of rhythms. The CD/BluRay version brings the added dimension of watching the musicians (playing in the round) in the moment, from a gently grooving Metropole harpist to Bobby Sparks II’s scorching clavinet/whammy bar solo on “Chimera” to Snarky’s four (!) drummers and three (!) percussionists playing off each other to ecstatic effect on postmodern blues “Recurrent”. The best capture of how immersive live music can be that I’ve seen and heard all year.

And crowding in just behind Mehldau and the Puppy is Touch, the return of Chicago arty post-rock pioneers Tortoise after a nine-year hiatus. Crisply, consistently melodic, the veteran quintet (including avant-jazz guitar ninja Jeff Parker) is subtly beguiling, even gentle at times; but the taut, understated rhythms and layers of textural grit underneath are what hold your attention. From the tolling “Layered Presence” through the ear-grabbing gear shifts of “Axial Seamount” and the squiggly/snarly/wispy “Oganesson” to the levitating movie-theme finale “Night Gang”, this is a fully collaborative vision, always straining toward unlimited vistas, pushing beyond the horizon of what most instrumental groups can conceive. Explore it along with Tortoise’s back catalog; I have a hunch you won’t be sorry!

And these other releases well worth checking out:

- Disquiet, three discs of extended, hypnotic studio improvs from the minimalist/ambient/jazz Australian piano trio The Necks.

- Motion II, where Blue Note Records all-star quintet Out Of/Into return with a fabulously consistent, frequently thrilling follow-up to last year’s excellent debut.

- Off the Record, the newest mash-up from drummer/beatmaster Makaya McCraven, collecting four digital EPs that span a decade. Taking live improvs alongside Tortoise’s Jeff Parker, Out Of/Into’s Joel Ross on vibraphone and British tuba virtuoso Theon Cross (among other huge talents) into the studio, McCraven works hip-hop production magic on dates from Los Angeles (PopUp Shop), hometown Chicago (Hidden Out!), London (Techno Logic) and New York (The People’s Mixtape) recomposing, overdubbing, flying in other instruments and looping key beats for maximum impact. The results are unstoppably propulsive, coolly thoughtful and thoroughly enjoyable even at their wildest.

- Joni’s Jazz, a four-disc offshoot of Joni Mitchell’s ongoing Archive series. Mitchell comes by her jazz pretensions honestly, claiming Miles Davis as an early muse, working with bass titan Charles Mingus in his final months, and regularly collaborating with Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter over the decades. There are more than a few tedious moments here, where Mitchell swaps out her melodic gift to climb on her lyrical soapbox;, but there are numerous highlights that compensate: check the loose swing of early classics like “Marcie” or “In France They Kiss On Main Street”; the numerous peaks of Mitchell’s genre explorations from Court and Spark through Mingus; later big-band collaborations (“Both Sides Now”); and oddities like “Love” and “The Sire of Sorrow (Job’s Sad Song)” where Mitchell languidly chants paraphrased Scripture while Shorter takes flight above her.

— Rick Krueger

Charles Lindbergh is simultaneously the most fascinating and the most frustrating individual I have ever encountered. Since December 2019, I have been cataloging the Missouri Historical Society’s collection of over 2000 objects that Lindbergh donated following his May 1927 New York to Paris flight. The collection ranges from artifacts carried on that flight to the hundreds of medals and awards he received, personal effects, artwork, two aircraft, jewelry, and the random gifts people and governments sent him or gave him and his wife, Anne, on their travels. In studying the material culture owned by and given to Lindbergh, I have learned a lot about him. Perhaps I have learned too much.

Charles Lindbergh is simultaneously the most fascinating and the most frustrating individual I have ever encountered. Since December 2019, I have been cataloging the Missouri Historical Society’s collection of over 2000 objects that Lindbergh donated following his May 1927 New York to Paris flight. The collection ranges from artifacts carried on that flight to the hundreds of medals and awards he received, personal effects, artwork, two aircraft, jewelry, and the random gifts people and governments sent him or gave him and his wife, Anne, on their travels. In studying the material culture owned by and given to Lindbergh, I have learned a lot about him. Perhaps I have learned too much.

You must be logged in to post a comment.