Hello, Spirit of Cecilia readers! Kevin J. Anderson has a Kickstarter campaign up and running for a gorgeous reissue of his Terra Incognita trilogy of fantasy novels and accompanying music that includes a new album from Roswell Six – Terra Incognita: Uncharted Shores. Brad Birzer, Rick Krueger, and Tad Wert share their thoughts on it.

Tad: Brad and Rick, I understand this is the third Terra Incognita album, but they haven’t been on my radar. What’s the story behind this group, and how are they connected to author Kevin Anderson?

Rick: Tad and Brad, it’s great to join you two for a roundtable at long last! I’m sure Brad knows a lot more about this project than I do. But I first came across Kevin Anderson when he and Neil Peart wrote a novel based on the Rush album Clockwork Angels. That one led to two more novels in the CA universe over the years, Clockwork Lives and Clockwork Destiny; all three of them were delightfully true to Peart’s concepts, with lots of clever Easter eggs from the Rush canon and enjoyable plot twists. The only other novel of Anderson’s I previously read is The Dark Between the Stars, the first part of a science fiction trilogy that was nominated for a Hugo award back in 2015 – solid, sprawling space opera fun. I’ve just downloaded his latest, Nether Station and am racing through it; he’s got that ever so slightly pulpy, lickety-split writing style down. it’s about a deep space expedition that, little by little, gets kinda eldritch . . .

But that really just scratches the surface of what Anderson has done. He’s most famous for continuing Frank Herbert’s Dune saga with Herbert’s son Brian; he’s also produced tie-in novels in the Star Wars, X-Files and DC universes; he’s an extremely prolific writer overall, whether it’s sci-fi, fantasy, horror or any combination of those genres – by his count, about 180 novels to date. On top of all that, he and his wife Rebecca Moeste run their own publishing company, WordFire Press.

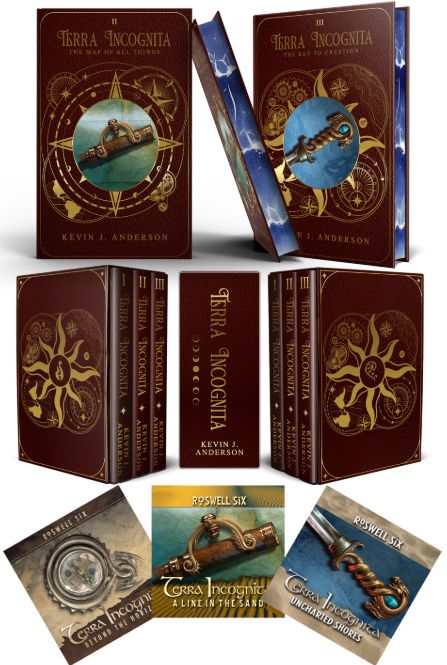

Through Brad’s connections with Anderson, I’m on WordFire’s mailing list, so I’ve noticed that he’s run a few Kickstarter campaigns over the years. His latest campaign is a reissue of Terra Incognita, a fantasy trilogy originally published in 2009-2011. The thing that’s different about these books, though, is that the first two had soundtracks; apparently, Anderson has had a lot of contact with the music world over the years. And maybe that’s where I should let Brad take over.

Brad: My dear friends, Tad and Rick, so great to do this with you guys! And, to talk about one of my all-time favorite human beings, Kevin J. Anderson. I’ve been reading Kevin’s works for years, but I only got to know him for the first time about 11 years ago. I had a one-year position at the University of Colorado-Boulder (2014-2015 academic year), and that position came with some funding to bring speakers in. As soon as I arrived in Longmont (where we lived for the year), I contacted Kevin (whom I had never met) and Dan Simmons. I never heard back from Simmons, but Kevin immediately agreed to come speak for me. He and his lovely (and equally talented) wife, Rebecca, came to Boulder, and Kevin gave an excellent speech on the art of writing fiction. He called it his “pop-corn theory,” explaining that ideas happen all over the place. I loved the speech.

And, I also loved Kevin and Rebecca. We hit it off at dinner at an Indian restaurant right before Kevin’s talk. He then invited us to his famous New Year’s Eve party for 2015. Dedra and I happily drove to Monument to see Kevin’s impressive and rather Arthurian house! Crazily enough, my car slid down his steep driveway and almost crushed the natural gas vein! Thank the good Lord that disaster was averted and New Year’s Eve was a different kind of blast. One of the great things about Kevin is he knows how to form communities. He’s a natural leader.

We also really bonded over his friendship with Neil Peart. In fact, it was Kevin who suggested I write the book about Peart’s lyrics, Cultural Repercussions, for his WordFire Press. I was deeply honored to do so not just because of my love of Rush, but also because of my respect for Kevin.

And, Kevin has deep roots in the prog rock community. Indeed, I can’t imagine a current writer who has greater or more legitimate ties to prog than does Kevin. Rush’s Grace Under Pressure inspired Kevin’s first novel, Resurrection, Inc., and Kevin’s never been shy about his inspirations: Rush, Kansas, Styx . . . .

Rick, you brought up Clockwork Angels and its surrounding universe. Admittedly, I love the Clockwork trilogy–the novels, the audiobooks, the graphic novels–and I think that Kevin really offered new insights into Rush and, frankly, into music. To me, Clockwork Angels is Chestertonian, and I don’t understand why it’s not been made a Netflix series!

When I first encountered Kevin’s music project, Roswell Six, I was understandably impressed by the scope as well as the execution of the vast project. Kevin has a great entrepreneurial spirit, but always with the artistic soul. Roswell Six perfectly blends Kevin’s many loves and expertises. I’ve been proudly listening to the first two CDs since they were first released, and I happily include them among my all-time favorite albums. I’m especially taken with the first CD, 2009’s Beyond the Horizon.

When Kevin first announced this Kickstarter project–hardback editions of Terra Incognita as well as a re-release of the first two Roswell Six CDs, AND a brand-new third CD, I was absolutely thrilled. I pledged during the second hour of the campaign. And, that campaign has done exceedingly well. Initially hoping to hit the $10,000 mark, the Kickstarter project, as of this writing, is at the $51,000 mark with 399 backers! Incredible. And, so well deserved.

So, what do you guys think of the music?

Tad: Okay, both of you have much more experience with Anderson’s work than I. When I saw that there was a companion novel to Rush’s Clockwork Angels, I immediately read it and enjoyed it very much. The Roswell Six albums slipped under my radar, though.

That said, I really like this third album, Terra Incognita (Uncharted Shores). To my ears, it’s pretty much straightforward, classic progrock. Fans of Kansas, Styx, Spock’s Beard, Threshold, Arena, et al. will love it. The fact that there are so many different vocalists brings to mind an Arjen Lucassen project – especially when the beautiful voice of Anneke van Geirsbergen appears in track 3, “A Sense of Wonder”.

I like the acoustic, Celtic sounding “Haunted and Hunted” a lot. “Lighthouse” is another highlight for me, with its chugging rock riffing and excellent guitar soloing. “The Ballet of the Storm” is an instrumental that has a very nice intro played on violin that transforms into a warm piano/electric guitar duet underpinned by some excellent bass.

“The Key to Creation” features the return of Anneke, and it has a fun 80s vibe to it – it’s got a relentless beat with a wall of synthesized sound. As a matter of fact, I think this is my favorite track on the album. It has a nice hook in the chorus that sticks in my ear.

“Unexpected” keeps the musical quality high with, I believe, Dan Reed handling the vocals. I feel like these songs will take on more meaning when I have the chance to read the accompanying novels. They obviously follow a storyline. In many of the tracks, I can hear sounds of the sea, which makes sense, given the Uncharted Shores title!

Rick: Brad, what you said about Anderson’s connections in the music world helped me get my bearings for listening to Uncharted Shores; it definitely has that American heartland prog vibe with some nifty touches of funk (but also touches of European theatricality, as Tad pointed out). KJA gave an interview this week with Michael Citro of Michael’s Record Collection where they go into the background behind the music; the basic tracks are written and performed by Bob Madsen (bass), Billy Connolly (guitar), Jerry Merrill (keys) and Gregg Bissonette (drums) – all artists working under the umbrella of The Highlander Company Records. (Madsen’s band The Grafenberg Disciples announced themselves to the world a few years back with a tribute to Peart, “No Words”, that caught Anderson’s attention.) And all that excellent violin work is by Jonathan Dinklage – he led the Clockwork Angels string section on those 2012 & 2013 tours. Rush connections aplenty!

The guest vocalists take the whole thing up a notch as well. Michael Sadler from Saga sings on the title song. “Hunted and Haunted” and “Lighthouse”; he’s played one of the “lead roles” for all three albums. Like you said, Tad, Ted Leonard and Anneke give it their all on their feature tracks. But the big surprise for me was Dan Reed, who takes the villain role on “Mortal Enemies” and “Unexpected”; for a minute, I thought Steve Walsh had emerged from retirement! Reed has this grizzled timbre, but a real purity of tone and expression underneath, and he absolutely sells the part. And The Grafenberg Disciples vocalist Hans Eberbach brings it all home on “Not In My Name” – gutsy and soulful by turns, and consistently dramatic (with Tull’s Doane Perry contributing a spoken-word cameo as a capper)! I think that’s the track that’s my favorite so far.

But there isn’t a duff song on the new album, and it definitely grew on me the second time through. I agree with you, Tad, that knowing the Terra Incognita storyline better will probably help, but the core emotions and throughline of the story come across loud and clear. According to the Anderson/Citro interview, all the albums are being released through Sony (on InsideOut?) in the fall, but I decided not to wait; I’ve pledged for the ebooks and the digital albums, so my summer reading and listening are already lined up. And when the CDs go to broad release – who knows? It’d be far from the first time I’ve bought music twice!

Brad: Tad and Rick, so well stated! And, yes, I pledged to buy all three albums as well, even though I already own the first two. If you’ve not listened yet, I especially recommend the first track on Beyond the Horizon: Ishalem. Incredible prog metal. Very much in line with Ayreon or Dream Theater.

For those out there not totally familiar with Kevin, he has, as noted above, written extensively in the Star Wars, Dune, and X-Files franchises. My favorite of his own books (that is, those not set in another mega genre/universe) are Nether Station (a sequel to H.P. Lovecraft’s Mountains of Madness) and Stake (a completely original novel questioning the existence of the supernatural).

Again, all praise to Kevin for bringing together so many beloved things: fantasy, science fiction, and prog rock!

Tad: Kevin Anderson’s Kickstarter link is here, for those interested!

You must be logged in to post a comment.