Book number 48 of 2024

The 80s are my favorite decade for music, when it seemed like all kinds of new styles were being created. In 1983, you could turn on the radio and hear hard rock, roots rock, soul, melodic pop, and electronic music all mixed together. My favorite genre from that era was (and is) synthpop, as epitomized by artists such as Depeche Mode, Gary Numan, Orchestral Maneuvers in the Dark, and Ultravox. Richard Evans has documented the birth and rise of electronic music from 1978 through 1983 in his massive tome (528 pages!), Listening to the Music the Machines Make. It’s a fascinating history of this primarily British musical movement.

Instead of relying exclusively on contemporary interviews of the artists, Evans went back to articles, reviews, and interviews that were published in the music press at the time the music was being released. He does have some recent interviews to support what his research uncovers, but for the most part he unearths reactions and thoughts of the artists when the music was fresh and new. This makes for an honest account that doesn’t rely on the memories of people who were creating this music more than 40 years ago.

Evans begins with describing the effect David Bowie had on British popular music when he unveiled his Ziggy Stardust persona on the BBC television show, Top of the Pops. Bowie’s innovation was to seem to look forward into the future to explain his music. This perspective, along with the availability of inexpensive synthesizers, opened the floodgates for a new wave of music. The short-lived punk movement added its manic energy and DIY aesthetic. All of these elements combined to create the perfect atmosphere in which to create music that was experimental, yet accessible.

Like Evans, I date “The 80s” from about 1977 to 1987. In 1977, I bought the Ramones’ Leave Home album, Talking Heads ’77, The Cars’ debut, Wire’s Pink Flag, as well as many other new wave albums. It was clear to my adolescent ears that drastic changes were happening in music – changes that would challenge the laid-back music of artists like The Eagles or the arena rock of Journey and Foreigner for popularity. Very quickly, the old guard of pop/rock were being supplanted by a host of new, innovative artists.

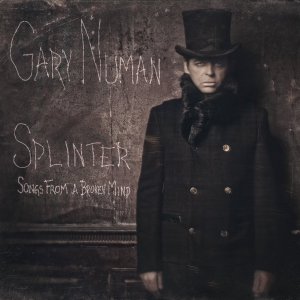

For me, things didn’t really get interesting until 1980/81. The electronic music produced before then (with the exception of Gary Numan, who, unsurprisingly, was the first big selling synthpop artist) was very experimental and often crude. Cabaret Voltaire, Fad Gadget, and early Ultravox just weren’t very tuneful. However, beginning in 1981, this musical movement began to really shake up the British pop charts. Once Midge Ure joined Ultravox, they became a formidable hit machine. 1981 is also the year Spandau Ballet, Duran Duran, and Depeche Mode released early hits.

Evans obviously did exhaustive research to write this book; it is divided into three main sections: Revolution (1978 & 1979), Transition (1980 & 1981), and Mainstream (1982 & 1983). He also includes a couple of shorter bookend chapters: Inspiration 1977 and Reaction 1984 – 1993. He must have read every issue of New Musical Express, Smash Hits, Record Mirror, Flexidisc, Melody Maker, and ZigZag from 1977 through 1983! I, personally, would have gotten depressed, because one thing that comes across loud and clear from Evans’ comprehensive and meticulous research is the sheer pettiness and shallowness of the British music press. I could cite hundreds of examples, but here are two:

‘Landscape make my flesh crawl, put snakes in my stomach and make my bowels twitch’, wrote Sounds’ Mick Middles. (page 248)

‘The only recognisable feature of Duran Duran is the singer’s voice, otherwise they have no personality, no individuality, no quirks of style. I think this is what is known in some quarters as “good pop”.’ (page 257)

If there’s one common characteristic of practically every reviewer, it’s resentment. As soon as an artist gains popularity, the music media turn on them and try their best to tear them down. Poor Gary Numan, who was the first electronic artist to break big, comes in for a savaging the rest of his career whenever he released a new album. When Blancmange had some chart success, Ian Pye in Melody Maker wrote,

“The K-Tel answer to Simple Minds, the revolting Blancmange have found themselves a mould and of course a shape follows. Pink, soft, and powdery to taste, this will remind you of school dinners and other things too unpleasant to mention here.” (page 361)

Time and time again, the reviewers neglect to actually describe and critique the music, instead going for a clever putdown.

That said, it is entertaining to read what the contemporaneous reactions were to albums that are today considered classics. Duran Duran’s Rio is now counted as one of the essential albums of the 80s, but it was pretty much dismissed in 1981. Ultravox’s Rage In Eden garnered a little more respect, but not much. One group that the consensus seemed to get right was Depeche Mode. Their first album with Vince Clarke, Speak and Spell, was well-crafted but disposable pop, and their album after Clarke left, A Broken Frame, was fairly lightweight. However, by the time Alan Wilder was integrated into the group and they released Construction Time Again, they were recognized as a significant force to be reckoned with.

Even though I am a big fan of this era and style of music, I still learned many new facts about the various artists: for example, the history of The Human League/Heaven 17 personnel, and their beginnings before the Dare and Penthouse and Pavement albums. I also learned that Peter Saville used a color code to include messages on New Order’s Blue Monday‘s and Power, Corruption, and Lies‘ cover art. Fascinating stuff for music nerds like myself!

Evans is a very good writer; he takes what could have been a boring recitation of musical history and turns it into a very entertaining account of some interesting personalities. If you ever wondered what the backstory was to huge hits like The Human League’s Don’t You Want Me or Gary Numan’s Cars, then Listening to the Music the Machines Make is the perfect resource. Evans has spent untold hours revisiting decades-old British music publications and organized the material into an essential reference. This is a book I’ll be returning to often, and I appreciate all of the work he put into it.

If you are interested in actually listening to the music Evans documents in his book, there is a Spotify playlist for each of the book’s main sections. (Hey, this is the 21st century, right?) They contain practically every song mentioned. I had a blast listening to the songs while reading about them. You can access the playlists here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.